|

Don’t Solve Problems; Seek Opportunities

Until Charles Darwin’s discovery of evolution, life was

surveyed in the present tense. Animals were probed to see how their

innards worked, plants dissected for useful magical potions, the

creatures of the sea investigated for their strange lifestyles. Biology

was about how living organisms thrived day to day.

Darwin forever transformed our understanding of life by

insisting that life didn’t make sense without the framework of its

billion-year evolution. Darwin proved that even if all we wanted to know

was how to cure dysentery in pigs, or how best to fertilize corn, or

where to look for lobsters, we had to keep in mind the slow, but

commanding dynamics of life’s evolution over the very long

term.

Until recently, economics was about how businesses thrived

year to year, and what kind of governmental policy to institute in the

next quarter. The dynamics of long-term growth are quite remote from the

issues of whether the money supply should be tightened this year. The

study of economics has no Darwin yet, but it is increasingly clear that

the behavior of everyday markets cannot be truly understood without

keeping in mind the slow, but commanding dynamics of long-term economic

growth.

Over the long run, the world’s economy has grown, on

average, a fractional percent per year. During the last couple of

centuries it averaged about 1% per year, reaching about 2% annually this

century, when the bulk of what we see on earth today was built. That

means that each year, on average, the economic system produces 2% more

stuff than was produced in the previous 12 months. Beneath the frantic

ups and downs of daily commerce, a persistent, invisible swell pushes

the entire econosphere forward, slowly thickening the surface of the

earth with more things, more interactions, and more opportunities. And

that tide is accelerating, expanding a little faster each year.

At the genesis of civilization, the earth was mostly

Darwin’s realm—all biosphere, no economy. Today the

econosphere is huge beyond comprehension. If we add up the total

replacement costs of all the roads in every country in the world, all

the railways, vehicles, telephone lines, power plants, schools, houses,

airports, bridges, shopping centers (and everything inside them),

factories, docks, harbors—if we add up all the gizmos and things

humans have made all over the planet, and calculate how much it is all

worth, as if it were owned by a company, we come up with a huge amount

of wealth accumulated over centuries by this slow growth. In 1998

dollars, the global infrastructure is worth approximately 4 quadrillion

dollars. That’s a 4 with 15 zeros. That’s a lot of pennies

from nothing.

What is the origin of this wealth? Ten thousand years ago

there was almost none. Now there is 4 quadrillion dollars worth. Where

did all of it come from? And how? The expenditure of energy needed to

create this fluorescence is not sufficient to explain it since animals

expend vast quantities of energy without the same result. Something else

is at work. "Humans on average build a bit more than they destroy,

and create a bit more than they use up," writes economist Julian

Simon. That’s about right, but what enables humans, on average, to

ratchet up such significant accumulations?

The ratchet is the Great Asymmetry, says evolutionist Steven

Jay Gould. This is the remarkable ability of evolution to create a bit

more, on average, than it destroys. Against the great drain of entropy,

life ratchets up irreversible gains. The Great Asymmetry is rooted in

webs, in tightly interlinked entities, in self-reinforcing feedback, in

coevolution, and in the many loops of increasing returns that fill an

ecosystem. Because every new species in life cocreates a niche for yet

other new species to occupy, because every additional organism presents

a chance for other organisms to live upon it, the cumulative total

multiplies up faster than the inputs add up; thus the perennial one-way

surplus of opportunities.

We call the Great Asymmetry in human affairs "the

economy." It too is packed with networks of webs that multiply

outputs faster than inputs. Therefore, on average, it fills up faster

than it leaks. Over the long run, this slight bias in favor of creation

can yield a world worth 4 quadrillion dollars.

It is not money the Great Asymmetry accrues, nor energy, nor

stuff. The origin of economic wealth begins in opportunities.

The first object made by human hands opened an opportunity

for someone else to imagine alternative uses or alternative designs for

that object. If those new designs or variations were manifested, then

these objects would create further opportunities for new uses and

designs. One actualized artifact yielded two or more opportunities for

improvement. Two improvements yielded two new opportunities

each—now there were four possibilities. Four yielded eight. Thus

over time the number of opportunities were compounded. Like the doubling

of the lily leaf, one tiny bloom can expand to cover the earth in

relatively few generations.

|

|

|

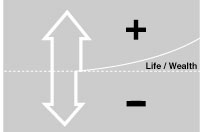

Both life and wealth expand by

compounding increase, which gives them an eternal slight advantage over

death and loss, so that over time there is constant growth. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perhaps the most potent physical force on earth is the power

of compounded results, whether that is compounded interest, compounded

growth, compounded life, or compounded opportunities. The inputs of

energy and human time into the economy can only be supplied in an

additive function, bit by bit, but over time the output is multiplied to

compound upon itself, yielding astounding accumulations.

A steady stream of human attention and thought is applied to

inventing new tools, devising new amusements, and creating new wants.

But no matter how small and inconsequential, each innovation is a

platform for yet other innovations to launch from.

It is this expanding space of opportunities that creates an

ongoing economy. It is this boundless open-ended arena for innovations

that spurs wealth creation. Like a chain reaction, one well-placed

innovation can trigger dozens, if not hundreds, of innovation offspring

down the line.

Consider, for example, email. Email is a recent invention

that has ignited a frenzy of innovation and opportunity. Each tiny bit

of email ingenuity begets several other bits of ingenuity, and they each

in turn beget others, and so on compoundfinitum. Unlike a piece of junk

mail, an email advertisement costs exactly the same to send to one

person or one million people—assuming you have a million addresses.

Where does one get a million addresses? People innocently post their

addresses all over the net—at the bottom of their home page, or in

a posting on a news group, or in a link off an article. These postings

suggested an open opportunity to programmers. One of them came up with

the idea of a scavenger bot. (A bot, short for robot, is a small bit of

code.) A scavenger bot roams the net looking for any phrase containing

the email @ sign, assumes it is an address, pockets it, and then

compiles lists of these addresses that are sold for $20 per thousand to

spammers—the folks who mail unsolicited ads (junk mail) to huge

numbers of recipients.

The birth of scavenger bots suddenly created niches for

anti-spam bots. Companies that sell internet access seed the net with

decoy phony email addresses so that when the addresses are picked up by

scavenger bots and used by the spammers, the internet provider will get

mail they can track to find out where the spam is coming from. Then the

provider blocks the spam from that source for all their customers, which

keeps everyone happy and loyal.

|

|

|

Each new invention creates a space

from which several more inventions can be created. And from each of

those new innovations comes yet more spaces of opportunity. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Naturally, that innovation creates opportunity for yet more

innovation. Creative spammers devised technology that allows them to

fake their source address; they hijack someone else’s legitimate

address to mail spam from and then flee after using it.

Every move generates two countermoves. Every innovation

creates an opportunity for two other innovations to succeed by it.

Every opportunity seized launches at least two new

opportunities.

The entire web is an opportunity dynamo. More than 320

million web pages have been created in the first five years of the

web’s existence. Each day 1.5 million new pages of all types are

added. The number of web sites—now at 1 million—is doubling

every 8 months. (Think lily pond!) A single opportunity seized in 1989

by a bored researcher began this entrepreneurial bloom. It is not the

lily leaf that is expanding now, but the lily pond itself.

The number of opportunities, like the number of ideas, are

limitless. Both are created combinatorially in the way words are. You

can combine and recombine the same 26 letters to write an infinite

number of books. The more components you begin with, the faster the

total possible combinations ramp up to astronomical numbers. Paul Romer,

an economist working on the nature of economic growth, points out that

the number of possible arrangements of bits on a CD is about 10^ billion.

Each arrangement would be a unique piece of software or music. But this

number is so huge there aren’t enough atoms in the universe to

physically make that many CDs, even subtracting all the duds that are

just random noise.

We can rearrange more than just bits. Think of the mineral

iron oxide, suggests Romer. It’s rust. More than 10,000 years ago

our ancestors used iron oxide as a pigment to make art on cave walls.

Now, by rearranging those same atoms into a precisely thin iron oxide

film on plastic we get a floppy disk, which can hold a reproduction of

the same cave paintings, and all the possible permutations of it wrought

by Photoshop. We have amplified the possibilities a millionfold.

The power of combinatorial explosions—which is what you

get with ideas and opportunities—means, says Romer,

"There’s essentially no scarcity to deal with." Because

the more you use opportunities, the less scarce they get.

Everything we know about the structu

re of the network economy suggests that it will bolster this

efflorescence of opportunities, for the following reasons:

- Every opportunity inhabits a connection. As we connect

up more and more of the world into nodes on a network, we make available

billions more components in the great combinatorial game. The number of

possibilities explodes.

- Networks speed the transmission of opportunities seized

and innovations created, which are disseminated to all parts of the

network and the planet, inviting more opportunities to build upon

them.

Technology is no panacea. It will never solve the ills or

injustices of society. Technology can do only one thing for us—but

it is an astonishing thing: Technology brings us an increase in

opportunities.

Long before Beethoven sat before a piano, someone with twice

his musical talents was born into a world that lacked keyboards or

orchestras. We’ll never hear his music because technology and

knowledge had not yet uncovered those opportunities. Centuries later the

fulfilled opportunity of musical technology gave Beethoven the

opportunity to be great. How fortunate we are that oil paints had been

invented by the time Van Gogh was ready, or that George Lucas could use

film and computers. Somewhere on Earth today are young geniuses waiting

for a technology that will perfectly match their gifts. If we are lucky,

they’ll live long enough for our knowledge and technology to make

the opportunity they need.

Oil paint, keyboard, opera, pen—all these opportunities

remain. But in addition we have added film, metal work, skyscrapers,

hypertext, and holograms as but a few of the new opportunities for

artistic expression. Each year we add more opportunities of every

stripe. Ways to see. Methods for thinking. Means of amusing. Paths to

health. Routes to understanding.

The Great Asymmetry of economic life ceaselessly amasses new

opportunities while relinquishing few old ones. The one-way journey is

toward more and more possibilities, pointing in more and more

directions, opening more and more new territories.

"A few decades from now there will be ten billion people

on the planet, and sophisticated computers will be cheaper than

transistor radios," writes science fiction writer David Brin in his

manifesto The Transparent Society. "If this combination does

not lead to war and chaos, then it will surely result in a world where

countless men and women swarm the dataways in search of something

special to do—some pursuit outside the normal range, to make each

one feel just a little bit extraordinary. Through the internet, we may

be seeing the start of a great exploration aimed outward in every

conceivable direction of interest or curiosity. An expedition to the

limits of what we are, and what we might become."

As the transmission of knowledge accelerates, as more

possibilities are manufactured, the unabated push of incremental growth

also speeds up. In the long run, creating and seizing opportunities is

what drives the economy. A better benchmark than productivity would be

to measure the number of possibilities generated by a company or

innovation and use the total to evaluate progress.

In the short run, though, problems must be solved. Businesses

are taught that they are in the business of solving problems. Put your

finger on a customer’s dissatisfaction, the MBAs say, and then

deliver a solution. This bit of hoary advice inspires business to seek

out problems. Problems, however, are entities that don’t work. They

are usually situations where the goal is clear but the execution falls

short. As in, "We have a reliability problem," or

"Customers complain about our late delivery." In the words of

Peter Drucker, "Don’t solve problems." George Gilder

distills the essence further: "When you are solving problems, you

are feeding your failures, starving your successes, and achieving costly

mediocrity. In a competitive global arena, costly mediocrity goes out of

business."

"Don’t solve problems; pursue

opportunities."

Seeking opportunities is no longer wisdom relevant only to

the long cycles of economic progress. As the economy speeds up, so that

an "internet year" seems to pass in one month, the principles

of long-term growth begin to govern the day-to-day economy. The dynamics

of growth become the dynamics of short-term competitive advantage.

In both the short and long term, our ability to solve social

and economic problems will be limited primarily to our lack of

imagination in seizing opportunities, rather than trying to optimize

solutions.

There is more to be gained by producing more opportunities

than by optimizing existing ones.

Optimization and efficiency die hard. In the past, better

tools made our work more efficient. So economists reasonably expected

that the coming information age would be awash in superior productivity.

That’s what better tools gave us in the past. But, surprisingly,

the technology of computers and networks have not yet led to measurable

increases in productivity.

Increasing efficiency brought us our modern economy. By

producing more output per labor input, we had more goods at cheaper

prices. That raised living standards. The productivity factor is so

fundamental to economic growth that it became the central economic

measurement tracked and perfected by governments. As economist Paul

Krugman once said, "Productivity isn’t everything, but in the

long run it is almost everything."

Productivity, however, is exactly the wrong thing to care

about in the new economy.

To measure efficiency you need a uniform output. But uniform

output is becoming rarer in an economy that emphasizes smaller

production runs, total customization, personalized "feelgoods"

and creative innovation. Less and less is uniform.

And machines have taken over the uniform. They love tedious

and measurable work. Constant upgrades enable them to churn out more per

hour. So the only ones who should worry about their own productivity are

those made of ball bearings and rubber hoses. And, in fact, the one area

of the current economy that does show a rise in productivity has been

the U.S. and Japanese manufacturing sectors, which have seen an

approximately 3% to 5% annual increase throughout the 1980s and into the

1990s. This is exactly where you want to find productivity. Each worker,

by supervising machinery and tools, produces more rivets, more

batteries, more shoes, and more items per person-hour. Efficiencies are

for robots.

Opportunities, on the other hand, are for humans.

Opportunities demand flexibility, exploration, guesswork, curiosity, and

many other qualities humans excel at. By its recursive nature, a network

breeds opportunities, and incidentally, jobs for humans.

Where humans are most actively engaged with their

imaginations, we don’t see productivity gains—and why would

we? Is a Hollywood movie company that produces longer movies per dollar

more productive than one that produces shorter movies? Yet an

increasingly greater percentage of work takes place in the information,

entertainment, and communication industries where the "volume"

of output is somewhat meaningless.

The problem with trying to measure productivity is that it

measures only how well people can do the wrong jobs. Any job that can be

measured for productivity probably should be eliminated from the list of

jobs that people do.

The task for each worker in the industrial age was to

discover how to do his job better: that’s productivity. Frederick

Taylor revolutionized industry by using his scientific method to

optimize mechanical work. But in the network economy, where machines do

most of the inhumane work of manufacturing, the question for each worker

is not "How do I do this job right?" but "What is the

right job to do?"

Answering this question is, of course, extremely hard to do.

It’s called an executive function. In the past, only the top 10% of

the workforce was expected to make such decisions. Now, everyone, not

just executives, must decide what is the right next thing to do.

In the coming era, doing the exactly right next thing is

far more fruitful than doing the same thing better.

But how can one easily measure this vital sense of

exploration and discovery? It will be invisible if you measure

productivity. But in the absence of alternative measures, productivity

has become a bugaboo. It continues to obsess economists because there is

little else they know how to measure consistently.

As bureaucrats continue to measure productivity, they find no

substantial increase in recent decades. This despite $700 billion

invested into computer technology worldwide each year. Millions of

people and companies worldwide purchase computer technology because it

increases the quality of their work, but in the aggregate there is no

record of their benefits in the traditional measurements. This

unexpected finding is called the productivity paradox. As Nobel laureate

Robert Solow once quipped, "Computers can be found everywhere

except in economic statistics."

There is no doubt that many past purchases of computer

systems were bungled, mismanaged, and squandered. Last year 8,000

mainframe computers—computers with the power of a Unix box and the

price of a large building—were sold to customers imprisoned by

legacy systems. IBM alone sold $5 billion worth of mainframes in 1997.

Those billions don’t help the efficiency ratings. The year 2000

fiasco is a world-scale screwup that also saps the payoff from

information technology. But according to economic historian Paul David,

it took the smokestack economy 40 years to figure out how to reconfigure

their factories to take advantage of the electric motor, invented in

1881; for the first decade of the changeover productivity actually

decreased. David likes to quip that "In 1900 contemporaries might

well have said that the electric dynamos were to be seen

‘everywhere but in the economic statistics.’ " And the

switch to electric motors was simple compared to the changes required by

network technology.

At this point we are still in just the third decade of the

age of the microprocessor. Productivity will rebound. In a few years it

will "suddenly" show up in elevated percentages. But contrary

to Krugman’s assertion, in the long run productivity is almost

nothing. Not because productivity increases won’t happen; they

will. But because, like the universal learning curve that brings costs

plunging down, increased productivity is a rote process.

The learning curve of inverted prices was first observed by

T. P. Wright, a legendary engineer who built airplanes after the First

World War. Wright kept records of the numbers of hours it took to

assemble each plane and calculated that the time dropped as the total

number of units completed increased. The more experience assemblers had,

the greater their productivity. At first this was thought to be relevant

only to airplanes, but in the 1970s engineers at Texas Instruments began

applying the rule to semiconductors. Since then the increase of

productivity with experience is seen everywhere. According to Michael

Rothschild, author of Bionomics, "Data proving learning-curve cost

declines have been published for steel, soft contact lenses, life

insurance policies, automobiles, jet engine maintenance, bottle caps,

refrigerators, gasoline refining, room air conditioners, TV picture

tubes, aluminum, optical fibers, vacuum cleaners, motorcycles, steam

turbine generators, ethyl alcohol, beer, facial tissues, transistors,

disposable diapers, gas ranges, float glass, long distance telephone

calls, knit fabric lawn mowers, air travel, crude oil production,

typesetting, factory maintenance, and hydroelectric power."

As the law of increasing productivity per experience was seen

to be universal, another key observation was made: The learning

didn’t have to take place within one company. The experience curve

could be seen across whole industries. Easy, constant communication

spreads experience throughout a network, enabling everyone’s

production to contribute to the learning. Rather than have five

companies each producing 10,000 units, network technologies allow the

five to be virtually grouped so that in effect there is one company

producing 50,000 units, and everyone shares the benefits of experience.

Since there is a 20% drop in cost for every doubling of experience, this

network effect adds up. Advances in network communications, standard

protocols for the transmission of technical data, and the informal, ad

hoc communities of technicians all spread this whirlwind of experience,

and ensures the routine rise of productivity.

Analyst Andrew Kessler of Velocity Capital Management

compares the plummeting of prices due to the universal learning curve to

a low pressure front in the economy. Just as a meterological low

pressure system sucks in weather from the rest of the country, the low

pressure point generated by sinking prices sucks in investments and

entrepreneurial zeal to create opportunities.

Opportunities and productivity work hand in hand much like

the two-step process of variation and death in natural selection. The

primary role that productivity plays in the network economy is to

disperse technologies. A technical advance cannot leverage future

opportunities if it is hoarded by a few. Increased productivity lowers

the cost of acquisition of knowledge, techniques, or artifacts, allowing

more people to have them. When transistors were expensive they were

rare, and thus the opportunities built upon them were rare. As the

productivity curve kicked in, transistors eventually became so cheap and

omnipresent that anyone could explore their opportunities. When ball

bearings were dear, opportunities sired by them were dear. As

communication becomes everywhere dirt cheap and ubiquitous, the

opportunities it kindles will likewise become unlimited.

The network economy is destined to be a fount of routine

productivity. Technical experience can be shared quickly, increasing

efficiencies in automation. The routine productivity of machines,

however, is not what humans want. Instead, what the network economy

demands from us is something that looks suspiciously like waste.

Wasting time and inefficiencies are the way to discovery.

When Condé Nast’s editorial director Alexander Liberman was

challenged on his inefficiencies in producing world-class magazines such

The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, and Architectural

Digest, he said it best: "I believe in waste. Waste is very

important in creativity." Science fiction ace William Gibson

declared the web to be the world’s largest waste of time. But this

inefficiency was, Gibson further noted, its main attraction and

blessing, too. It was the source of art, new models, new ideas,

subcultures, and a lot more. In a network economy, innovations must

first be seeded into the inefficiencies of gift economy to later sprout

in efficiencies of the commerce.

Before the World Wide Web there was Dialog. Dialog was pretty

futuristic. In the 1970s and ’80s it was the closest thing to an

electronic library there was, containing the world’s scientific,

scholarly, and journalistic texts. The only problem was its price, $1

per minute. You could spend a lot of money looking things up. At those

prices only serious questions were asked. There was no fooling around,

no making frivolous queries—like looking up your name. Waste was

discouraged. Since searching was sold as a scarcity, there was little

way to master the medium, or to create anything novel.

It takes 56 hours of wasting time on the web—clicking

aimlessly through dumb web sites, trying stuff, and making tons of

mistakes and silly requests—before you master its search process.

The web encourages inefficiency. It is all about creating opportunities

and ignoring problems. Therefore it has hatched more originality in a

few weeks than the efficiency-oriented Dialog system has in its

lifetime, that is, if Dialog has ever hatched anything novel at all.

The Web is being run by 20-year-olds because they can afford

to waste the 56 hours it takes to become proficient explorers. While

45-year-old boomers can’t take a vacation without thinking how

they’ll justify the trip as being productive in some sense, the

young can follow hunches and create seemingly mindless novelties on the

web without worrying about whether they are being efficient. Out of

these inefficient tinkerings will come the future.

Faster than the economy can produce what we want, we are

exploring in every direction, following every idle curiosity, and

inventing more wants to satisfy. Like everything else in a network, our

wants are compounding exponentially.

Although at some fundamental level our wants connect to our

psyches, and each desire can be traced to some primeval urge, technology

creates ever new opportunities for those desires to find outlets and

form. Some deep-rooted human desires found expression only when the

right technology came along. Think of the ancient urge to fly, for

instance.

KLM, the official Dutch airline, sells a million dollars

worth of tickets per year to people who fly trips to nowhere. Customers

board the plane on whatever international flight KLM has extra seats on,

and make an immediate round-trip flight, returning without leaving the

airport at the other end. The flight is like a high-tech cruise, where

duty-free shopping and simply flying in a 737 at a steep discount is the

attraction. Where did this want come from? It was created by

technology.

Finance writer Paul Pilzer notes perceptively that "When

a merchant sells a consumer a new Sony Walkman for $50, he is in fact

creating far more demand than he is satisfying—in this case a

continuing and potentially unlimited need for tape cassettes and

batteries." Technology creates our needs faster than it satisfies

them.

Needs are neither fixed nor absolute. Instead they are fluid

and reflexive. The father of virtual reality, Jaron Lanier, claims that

his passion for inventing VR systems came from a long-frustrated urge to

play "air guitar"—to be able to wave his arms and have

music emanate from his motions. Anyone with access to a VR arcade can

now have that urge satisfied, but it is a want that most people would

have never recognized until they immersed themselves into virtual

reality gear. It was certainly not a primary want that Plato would have

listed.

At one time a useful distinction was made in economics

between "primary" needs such as food and clothing, and all

other wants and preferences, which were termed "luxuries."

Advertising is undoubtedly guilty, as critics charge, of creating

desires. At first these manufactured desires were for luxuries. But the

reach of technology is deep. Sophisticated media technology first

creates desires for luxuries; then technology transforms those luxuries

into primary necessities.

A dry room with running water, electric lights, a color TV,

and a toilet are considered so elementary and primary today that we

outfit jail cells with this minimum technology. Yet three generations

ago, this technology would have been officially classified as outright

luxurious, if not frivolous. In the government’s eyes 93% of

Americans officially classified as living in poverty have a color TV,

and 60% have a VCR and a microwave. Poverty is not what it used to be.

Technological knowledge constantly ups the ante. Most Americans today

would find living without a refrigerator and telephone to be primitive,

indeed. These items were luxuries only 60 years ago. At this point an

automobile of one’s own is considered a primary survival need of

any adult.

"Need" is a loaded word. The key point in economic

terms is that each actualization of a desire—that is, each new

service or product—forms a platform from which other possible

activities can be imagined and desired. Once technology satisfies the

opportunity to fly, for instance, flying produces new desires: to eat

while flying, to fly by oneself to work each day, to fly faster than

sound, to fly to the moon, to watch TV while flying. Once technology

satisfies the desire to watch TV while flying, our insatiable

imagination hungers to be able to watch a video of our own choosing, and

to not see what others watch. That dream, too, can be actualized by

technical knowledge. Each actualization of an idea supplies room for

more technology, and each new technology supplies room for more ideas.

They feed on each other, rounding faster and faster.

This ever-extending loop whereby technology generates

demand, and then supplies the technology to meet those demands is the

origin of progress. But it is only now being viewed as such. In

classical economics—based on the workings of the brick and

smokestack—technology was a leftover. To explain economic growth,

economists tallied up the effects of the traditional economic

ingredients such as labor, capital, and inventory. This aggregate became

the equation of growth. Whatever growth was not explained by those was

attributed to a residual category: technology. Technology was thus

defined as outside the economic engine. It was also assumed to be a

fixed quantity—something that didn’t really change itself.

Then in 1957 Robert Solow, an economist working at MIT, calculated that

technology is responsible for about 80% of growth.

We see now, particularly with the advent of the network

economy, that technology is not the residual, but the dynamo. In the new

order, technology is the Prime Mover.

Our minds will at first be bound by old rules of economic

growth and productivity. Listening to the technology can loose them.

Technology says, rank opportunities before efficiencies. For any

individual, organization, or country the key decision is not how to

raise productivity by doing the same better, but how to negotiate among

the explosion of opportunities, and choose right things to do.

The wonderful news about the network economy is that it plays

right into human strengths. Repetition, sequels, copies, and automation

all tend toward the free and efficient, while the innovative, original,

and imaginative—none of which results in efficiency—soar in

value.

Strategies

Why can’t a machine do this? If there is pressure

to increase the productivity of human workers, the serious question to

ask is, why can’t a machine do this? The fact that a task is

routine enough to be measured suggests that it is routine enough to go

to the robots. In my opinion, many of the jobs that are being fought

over by unions today are jobs that will be outlawed within several

generations as inhumane.

Scout for upside surprises. The qualities needed to

succeed in the network economy can be reduced to this: a facility for

charging into the unknown. Disaster lurks everywhere, but so do

unexpected bonanzas. But the Great Asymmetry ensures that the upside

potential outweighs the downside, even though nine out of ten tries will

fail. Upside benefits tend to cluster. When there are two, there will be

more. A typical upside surprise is an innovation that satisfies three

wants at once, and generates five new ones, too.

Maximize the opportunity cascade. One opportunity

triggers another. And then another. That’s a rifle-shot opportunity

burst. But if one opportunity triggers ten others and those ten others

after, it’s an explosion that cascades wide and fast. Some seized

opportunities burst completely laterally, multiplying to the hundreds of

thousands in the first generation—and then dry up immediately.

Think of the pet rock. Sure, it sold in the millions, but then what?

There was no opportunity cascade. The way to determine the likelihood of

a cascade is to explore the question: How many other technologies or

businesses can be started by others based on this opportunity?

continue...

|