|

Members Prosper as the Net Prospers

The distinguishing characteristic of networks is that they

contain no clear center and no clear outside boundaries. Within a

network everything is potentially equidistant from everything else.

Therefore the first thing the network economy reforms is

our identity.

The vital distinction between the self (us) and the nonself

(them)—once exemplified by the fierce loyalty of the organization

man in the industrial era—becomes less meaningful in a network

economy. The only "inside" now is whether you are on the

network or off.

Individual allegiance moves away from firms and toward

networks and network platforms.

Are you Windows or are you Mac?

This shift to network loyalty makes the potential of any

network we might want to join a key issue. Is the network waxing or

waning? Is the upside potential meager or tremendous? Is the network

open or closed?

When given the choice between closed or open systems,

consumers show a fierce enthusiasm for open architectures. They choose

the open again and again because an open system has more potential

upside than a closed one. There are more sources from which to recruit

members and more nodes with which to intersect.

Identifying the preferred network to do business in is now a

major chore for firms. Because more and more of a firm’s future

lies in its networks, firms must evaluate a network’s relative

open- and closedness, its circulation, its ability to adapt. Consultant

John Hagel says, "A web limits risk. It allows companies to make

irreversible investments in the face of technological uncertainty.

Companies in a web enjoy expanding sourcing and distribution options,

while their fixed investment and skill requirements fall."

As the destiny of firm and web intertwine, the health of

the matrix becomes paramount.

Maximizing the value of the net itself soon becomes the

number one strategy for a firm. For instance, game companies will devote

as much energy to promoting the platform—the tangle of users, game

developers, and hardware manufacturers—as they do to their games.

For unless their web thrives, they die. This represents a momentous

change—a complete shift in orientation. Formerly, employees of a

firm focused their attention on two loci: the firm itself and the

marketplace.

|

The prosperity of a firm is directly linked to the prosperity of its

network. As the platform or standard it operates on flourishes, so does

the firm. |

Now there is a third horizon to consider: the network. The

network consists of subcontractors, vendors and competitors, emerging

standards for exchanges, the technical infrastructure of commerce, and

the web of consumers and clients.

Commerce networks can be thought of as ecologies. Economist

Brian Arthur states: "Players compete not by locking in a product

on their own but by building webs—loose alliances of companies

organized around a mini-ecology—that amplify positive feedbacks to

the base technology."

During certain phases of growth, feeding the network is as

important as feeding the firm. Some firms that already have large market

shares (such as Intel, which owns 80% of the PC processor market)

channel money, through minority investments, to younger firms whose

success will strengthen the market for their products, directly or

indirectly. They feed the web because it is good business.

In the network economy a firm’s primary focus shifts

from maximizing the firm’s value to maximizing the network’s

value.

Not every network demands the same investment. The music CD

standard and web of suppliers is well entrenched by now. The new DVD

video standard is not. A publishing company issuing music on a CD has to

devote less energy to making sure the CD platform flourishes than does a

movie company issuing their film on a DVD. The film company must devote

substantial resources to ensuring the spread and survival of this

emerging platform. They’ll work with the hardware manufacturers,

maybe share costs of advertising by seeding the platform logo in their

own ads, send reps to technical committees, and cooperate with other

film studios in getting the new format accepted. The music company

doesn’t need to make as heavy an investment with CDs. But they do

need to make investments into new networks if they try to deliver music

online—because online delivery is still in its embryonic phase.

Every network technology follows a natural life cycle,

roughly broken into three stages:

- Prestandard

- Fluid

- Embedded

A firm’s strategy will depend on what phase a network is

in.

The prestandard phase is the most exciting. This period is

marked by tremendous innovation, high hopes, and grand ambition.

"Aha!" ideas flow readily. Since there are no experts,

everyone can compete, and it seems as if everyone does. Easy entry into

the field draws myriad players. For instance, when telephone networks

began, there were few standards and many contenders. In 1899, there were

2,000 local telephone firms in the American telephone network, many of

them running with their own standards of transmission. In a similar

vein, in the 1890s, electricity came in a variety of voltages and

frequencies. Each local power plant chose one of many competing

standards for electrical power. Transportation networks, ditto. As late

in the railroad era as 1880, thousands of railway companies did not

share a universal gauge.

Two examples of networks in the prestandard stage today are

online video and e-money. You have the choice of many competing

protocols with equal prospects. With both domains, the uncertainty level

is high, but the consequences of being wrong are minimal. Little is

locked in, so it’s easy to change.

Networks in the fluid phase have a different dynamic. The

plethora of choices in the prestandard phase gradually reduces to two or

three. Allegiances are mobile, and drift over time. During this period,

networks demand the strongest commitment to their survival. Participants

have to feed the web of their choice first, and the narrowing of choices

allows substantial investment to spur rapid growth. The effects of

plentitude and increasing returns kick in—more breeds more. Feeding

the web on any of several standards still produces gains for all

participants. Yet it is inevitable that only one standard will

ultimately prevail while the other ones fail. The uncertainty level is

nearly as high as during the prestandard phase, but the risks for being

wrong are greater. Anyone who remembers the demise of 8-track audiotapes

will appreciate the perils of this painful stage. Today such networks as

digital photographs and desktop operating systems are in this fluid

phase: Several well-established standards vie for ultimate dominance.

Choose wisely!

The final stage in the life cycle of networks is the

embedded phase, where one standard is so widely accepted that it becomes

embedded in the fabric of the technology and is thereafter nearly

impossible to dislodge—at least as long as the network exists.

Regular 110-volt AC power is well embedded at this point (although, as

the power grid becomes global, there could be some surprises). ASCII

text is likewise deeply embedded—at least for phonetic languages.

Some of the conventions of voice dial tone are so ubiquitous worldwide

as to be permanent.

In any phase of innovation—prestandard, fluid, or

embedded—standards are valuable because they hasten innovation.

Agreements are constraints on uncertainty. The constraints of a standard

solidify one pathway out of many, allowing further innovation and

evolution to accelerate along that stable route. So central is the need

to cultivate certainty that organizations must make the common standard

their first allegiance. As standards are established, growth takes

off.

For maximum prosperity, feed the web first.

Arriving at standards is often easier said than done.

Standard-making is a torturous, bickering process every time. And the

end result is universally condemned—since it is the child of

compromise. But for a standard to be effective, its adoption must be

voluntary. There must be room to dissent by pursuing alternative

standards at any time.

Standards play an increasingly vital role in the new

economy. In the industrial age, relatively few products demanded

standards. You didn’t need a consensual network to make a chair and

table. If you obeyed some basic ergonomic conventions—make table

height 30 inches—you were on your way. Those industrial products

that operated in networks—such as the electrical or transportation

networks—demanded sophisticated standard-making. Anything plugged

into the electrical grid had to be standard. Automobiles manufactured by

separate factories shared standards on such things as axle width, fuel

mixtures, placement of turn signals, not to mention the many standards

of road construction and signage.

All information and communication products and services

demand extensive consensus. Participants at both ends of any

conversation have to understand each other’s language. Multiply one

conversation by a billion, factor in a thousand different media choices,

and then start to count three-way, four-way, n-way conversations,

and the amount of consensus-setting skyrockets.

In the network economy, ever-less energy is needed to

complete a single transaction, but ever-more effort is needed to agree

on what pattern the transaction should follow.

Thus "feeding the web first" increases in

necessity. Businesses can expect to devote great intellectual capital

on formulating, negotiating, deciding, forecasting, and adhering to

emerging standards. The question "Which platform do we back?"

will not be confined to PCs. It will be asked in regard to calendars,

cars, accounting principles, and even currencies.

As more of the economy migrates to intangibles, more of

the economy will require standards.

But consumers will groan under the load of decisions. There

is a yin-yang tradeoff in the new economy. The yin, or positive side, is

that consumers keep most of the gains in productivity that are earned

by technology. Competition is so severe, and transactions so

"friction-free," that most of each cycle’s betterment

goes not to corporate profits but to consumers in the form of cheaper

prices and higher quality.

The yang, or downside, is that consumers have a never-ending

onslaught of decisions to make about what to buy, what standard to join,

when to upgrade or switch, and whether backward compatibility is more

important than superior performance. The fatigue of sorting out options

and allegiances, or recovering from them, is underappreciated at the

moment, but will mount. The joy of the new economy is that the next

version is almost free; the bane is that no one wants the hassle of

upgrading to it, even if you pay them to do it.

The fatigue will only worsen. The net is a possibility

factory, churning out novel opportunities by the screenful. Unharnessed,

this explosion can drown the unprepared. Standardizing choices helps

tame the debilitating abundance of competing possibilities. This is why

the most popular sites on the web today are meta-sites that sort the

abundance and point you to the best.

Since the network economy is so new, we as a society have

paid little attention to how standards are created and how they grow.

But we should notice, because once implemented, a successful standard

tends to remain forever. And standards themselves shape behavior.

I was associated with the genesis of the Well, one of the

first public computer conferencing systems to be plugged into the

internet. The Well was conceived and built by others, but as director of

the poor nonprofit that owned it, and as one of the first participants

to join when it opened, I was involved in creating its policies. It

became clear almost from day one that the technical specifications of

the software that the Well used directly shaped the kind of community

growing within it. Other models of conferencing software used elsewhere

produced different kinds of communities. The Well’s

software—as implemented by the Well—encouraged linear

conversations and community memory; it discouraged anonymity, but

encouraged responsibility for words and topics; it permitted limited

forms of dissent and retraction, and it allowed users to invent their

own tools. It did all this primarily by means of Unix code—by the

software standards set up within the Well—rather than by posted

rules. The community it shaped was distinctive and long-lived. In fact

the community, with all its quirks, is still going, even though the

software that runs it has evolved into a web browser interface. The

behavior-changing standards remain. The power to mold a community by

code rather than regulation was eventually articulated by Well users

into a serviceable maxim: Peace through tools, not rules.

The internet and the web also contain toolish standards that

invisibly shape our behavior. We have ideas about ownership, about

accessibility, about privacy, and about identity that are all shaped by

the code of HTML and TCP/IP, among others. Currently only a small

portion of our lives flow through these webs, but as cyberspace

subsumes televisionspace and phonespace and much of retailspace, the

influence of standards upon social behavior will grow.

Eventually technical standards will become as important as

laws.

Laws are codified social standards; but in the future,

codified technical standards will be just as important as laws. Harvard

Law professor Lawrence Lessig says, "Law is becoming irrelevant.

The real locus of regulation is going to be (computer) code." As

networks mature, and make the transition from ad hoc prestandard

free-for-alls to fluid hot spots of innovation, and then into

full-fledged systems with deeply embedded standards, standards

increasingly ossify into something like laws.

Standards also harden with age. They become resistant to

change and they descend into hardware. Their code gets wired into

the backs of chips, and as the chips spread, the standard infiltrates

ever more deeply.

An elaborate process of legal overview monitors and analyzes

our lawmaking. So far we have little of the sort for our

standard-making, although these agencies, such as the ITU

(International Telecom Union) will soon be as influential as courts.

Standards are not just about technology. They are about soft and fuzzy

things such as options and relationships and trust. They are social

instruments. They create social territory.

A network is like a country in that it is a web of

relationships regulated by standards. In a country citizens pay taxes

and adhere to laws for the benefit of all. In a network, netizens feed

the web first for the benefit of all. The network economy is a

meta-country. Its web of relationships differ from those of a country in

three ways:

- No geographical or temporal boundaries

exist—relations flow ceaselessly 24 by 7 by 365.

- Relations in the network economy are more tightly

coupled, more intense, more persistent, more diverse, and more intimate

in many ways than most of those in a country.

- Multiple overlapping networks exist, with multiple

overlapping allegiances.

These hyperconnections can either strengthen or weaken

traditional relationships. The extremely personal, highly trust-bound

relations in a family stand to be strengthened, while the diffuse and

nearly contractual relations in a nation-state are liable to weaken.

Yet, as Peter Drucker points out, "The nation-state is not going to

wither away. It may remain the most powerful political organ around for

a long time to come, but it will no longer be the indispensable

one." In its stead we’ll rely on nongovernmental agencies such

as the Red Cross, ACLU, HMOs, insurance giants, the net and the web, and

UN-like entities. These parapolitical organizations will supplement the

embedded nation-state. They will be the indispensable networks we care

about.

In both country and network, the surest route to raising

one’s own prosperity is raising the system’s prosperity. The

one clear effect of the industrial age is that the prosperity

individuals achieve is more closely related to their nation’s

prosperity than to their own efforts. Lester Thurow, an MIT economist,

has pointed out that enabling the lowest paid to earn more is the best

way to raise wages for the highest paid—the theory being that a

rising tide lifts all boats. The network economy will only amplify

this.

To raise your product, lift the networks it ties into. To

raise your company, lift the standards it supports. To raise your

country, increase the connections (in quality and quantity) that allow

others to prosper.

To prosper, feed the web first.

The web is underfed right now. It is small compared to the

rest of the world. In 1998 the internet boasted of an estimated 120

million people with access. But that means only 2% of human adults have

a direct line to the online network.

But the net is growing exponentially fast. If current rates

continue, by early in the new century, 1 billion people will have

internet access, 75% of adults will access to some kind of phone, and,

according to Nicholas Negroponte, there will be 10 billion electronic

objects connected together online. Every year the net engulfs more of

the world.

The net is moving irreversibly to include everything of

the world.

As the net takes over, many observers have noted the gradual

displacement in our economy of materials by information. Automobiles

weigh less than they once did and yet perform better. Industrial

materials have been replaced by nearly weightless high-tech know-how in

the form of plastics and composite fiber materials. Stationary objects

are gaining information and losing mass, too. Because of improved

materials, high-tech construction methods, and smarter office equipment,

new buildings today weigh less than comparable ones from the 1950s. So

it isn’t only your radio that is shrinking, the entire economy is

losing weight too.

|

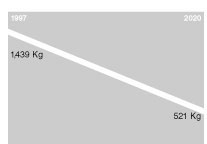

Even industrial objects like atuomobiles follow new rules. An

automobile's average weight is dropping and will continue to drop as

information replaces its mass. |

Even when mass is conserved, information increases. An

average piece of steel manufactured in 1998 was vastly different from an

average piece of steel made in 1950. Both pieces weighed approximately

the same, but the one made recently is far superior in performance

because of the amount of design, research, and knowledge that went into

its creation. Its superior value is not due to extra atoms, but to

extra information.

The wholesale migration from mass to bits began with the

arrival of computer chips. This subtle disembodiment was first viewed as

a unique dynamic of the high-tech corridors of Silicon Valley. Software

was so strange—part body, part spirit—that nobody was

surprised when the computer industry itself behaved strangely. The

principles of the net, such as increasing returns, were seen as special

cases, anomalies within the larger "real" economy of steel,

oil, automobiles, and farms. What did such weirdness have to do with,

say, making cars, or selling lettuce? At first, nothing. But by now

every industry (shoe retail, glass manufacturing, hamburgers) has an

information component, and that component is increasing. There is not a

single company of consequence that does not use computers and

communication technology. All U.S. companies (low as well as high-tech)

together spent $212 billion on information technology in 1996. Often,

the digital component of the firm, say the IT or MIS department, or the

wizards running the technology, will be the first to feel the influence

of the new rules and network dynamics. Consultants Larry Downes and

Chunka Mui say, "Even though the primary technology of many

industries may not be in transition ... every industry is going

through a revolution in its information technology." As more of a

company "goes online" nerd ideas begin to seep into the whole

organization, reshaping the firm’s understanding of what it is

doing. Over time, more and more employees will chase the opportunities

that intensive information and communication networks bring.

New network technology and globalization accelerates the

disembodiment of goods and services. The new dynamics of information

will gradually supersede the old dynamics of industrialization until

network behavior becomes the entire economy.

Bit by bit, the logic of the network will overtake every

atom we deal with.

The logic of the network will spread from its base in silicon

chips, to infiltrate steel, plywood, chemical dyes, and potato chips.

All manufacturing, whether seeded with silicon wafers or not, will

respond to network principles.

Consider oil—the quintessential atom-based resource. The

classical theory of diminishing returns was practically invented to

explain the oil industry. Easy oil is extracted cheaply at first; then

at a certain point the expense of extraction doesn’t justify the

cost unless the price goes up. But by now the oil industry is so invaded

by chip technology that it is beginning to obey the laws of the new

economy. Sophisticated 3D viewing software allows geologists to map

oil-yielding layers to within a few meters; computer-guided flexible

drills can burrow sideways with precision, reaching small pockets of

oil. Superior pumps extract more oil with less energy and maintenance.

Diminishing returns are halted. The oil flows steadily at steady prices,

as the oil industry slides into the new economy.

And what could be more industrial-age than automobiles? Yet,

chips and networks can take the industrial age out of cars, too. Most of

the energy a car consumes is used to move the car itself, not the

passenger. So if the car’s body and engine can be diminished in

size, less power is needed to move the car, meaning the engine can be

made yet smaller. A smaller engine requires a yet smaller engine, and so

on down the slide of compounded value that microprocessors followed. The

car’s body can be reduced substantially using smart

materials—stuff that requires increasing knowledge to invent and

make—which in turn means a smaller, more efficient engine can power

it.

Detroit and Japan have designed cars that weigh only 500

kilograms. Built out of ultra-lightweight composite fiber material,

these prototypes are powered by high-tech hybrid engine motors. They

reduce the mass of radiator, axle, and driveshaft by substituting

networked chips. They insert chips to let the car self-diagnose its

performance, in real time. They put chips in brakes, making them less

likely to skid. They put microprocessors in the dashboard to ease

navigation and optimize fuel use. They use hydrogen fuel cells that do

not pollute, and electric motors with low noise pollution. And just as

embedding chips in brakes made them better, these lightweight cars will

be wired with network intelligence to make them safer: A crash will

inflate intelligent multiple air bags—think "smart

bubblepak."

The accumulated effect of this substitution of knowledge for

material in automobiles is what energy visionary Amory Lovins, director

of the Rocky Mountain Institute, calls a hypercar: an automobile that

will be safer than today’s car, yet can cross the continental

United States on one tank of hydrogen fuel.

Already, the typical car boasts more computing power than

your typical desktop PC. Already the electronics in a car cost more

($728) than the steel in the car ($675). But what the hypercar promises,

says Lovins, is a car remade by silicon. A hypercar can be viewed as

step toward a vehicle that is (and behaves like) a solid state module. A

car becomes not wheels with chips, but a chip with wheels. And this chip

with wheels will drive on a road system increasingly wired as a

decentralized electronic network obeying the network economy’s laws

as well.

Once we visualize cars as chips with wheels, it’s

easier to imagine airplanes as chips with wings, farms as chips with

soil, houses as chips with inhabitants. Yes, they will have mass, but

that mass will be subjugated by the overwhelming amount of knowledge

and information flowing through it. In economic terms, these objects

will behave as if they had no mass at all. In that way, they migrate to

the network economy.

Because information trumps mass, all commerce migrates to

the network economy.

MIT Media Lab director Nicholas Negroponte guesstimates that

the online economy will have reached $1 trillion by 2000. Most tenured

economists think that figure is terribly optimistic. But actually that

optimistic figure is terribly underestimated. It doesn’t anticipate

the scale on which the economic world will move on to the internet as

the network economy infiltrates cars and traffic and steel and corn.

Even if all cars aren’t sold online immediately, the way cars are

designed, manufactured, built, and operated will depend on network logic

and chip power.

The current concern about the size of the online market will

have diminishing relevance, because all commerce is jumping on to

the internet. The distinctions between the network economy and the

industrial economy will likewise blur and fade, as all economic activity

is touched in some way by network rules. The key distinction remaining

will be between the animated versus the inert.

The realm of the inert encompasses any object that is

divorced from its economic information. A head of lettuce today for

instance does not contain any financial information beyond a price

sticker. Once applied, that price is fixed, too. It doesn’t change

unless a human changes it. The economic consequences of lettuce sales

elsewhere, or a change in the general global economy do not affect the

head of lettuce itself. Instead, lettuce-related information flows

through wholly separate channels—news programs or business

newsletters—that are divorced from the lettuce itself. The lettuce

is economically inert.

The realm of the animated is different. It’s vastly

interconnected. In this coming world a head of lettuce carries its own

identity and price, displayed perhaps on an LED slab nearby, or on a

disposable chip attached to its stem. The price changes as the lettuce

ages, as lettuce down the street is discounted, as the weather in

California changes, as the dollar surges in relation to the Mexican

peso. Traders back in supermarket headquarters manage the

"yield" of lettuce prices using the same algorithms that

airlines use to maximize their profits from airline seats. (An unsold

seat on a 747 is as perishable as an unsold head of lettuce.) In

relation to the net, the lettuce is animated. It is dynamic, adaptive,

and interacting with events. A river of money and information flows

through it. And if money and information flow through something, then

it’s part of the network economy.

The progression by which the old economy migrates toward the

new follows a relentless logic:

- Increasing numbers of inert objects are animated by

information networks.

- Once the inert is touched by a network, it obeys the

rules of information.

- Networks don’t retreat; they tend to multiply into

new territories.

- Eventually all objects and transactions will run by

network logic.

One is tempted to add "resistance is futile." The

overwhelming long-term trend toward universal connection may seem

Borg-like, as if all things will lose their identity and become part of

one large mindless swarm. Two things should be made clear: 1) constant,

ubiquitous connections do not per se eliminate individuality; and 2) by

"all" I mean an ongoing trend that approaches an asymptote,

not a finality.

One might say that industrialization eradicated hand-crafted

production to the point where all objects are machine-made. That

is true by and large, and it accurately describes the destination of a

trend. But the trend has a few notable exceptions. In an era of objects

made completely by machines, hand-made items are a scarcity and thus

command very high prices. A few—but only a few—shrewd artisans

and entrepreneurs can make a living crafting items by hand, items such

as bicycles, furniture, guitars, that would ordinarily be stamped out in

a factory. Resistance is marginal, but profitable.

The same will be true in the networking of the economy.

Resistance will not be futile. In a world of ubiquitous connection,

where everything is connected to everything else, scarce will be the

person not connected at all, or the company not pushing ideas and

intangibles. If these mavericks are able to interface with the networked

economy without losing their distinctivness or value, then they will be

sought out, and their products priced high. One can imagine a successful

idea-artist in the year 2005 who does no email, no phone, no

videoconferences, no VR, no books, and who does not travel. The only way

to get her fabulous ideas is in person, face-to-face at her hideout,

live. The fact that she is booked 8 months in advance only adds to her

reputation.

MIT economist Paul Krugman has an alternative vision of how

information technology will invert the expected order. He writes:

"The time may come when most tax lawyers are replaced by expert

systems software, but human beings are still needed—and well

paid—for such truly difficult occupations as gardening, house

cleaning, and the thousands of other services that will receive an

ever-growing share of our expenditure as mere consumer goods become

steadily cheaper." Actually we don’t need to wait for the

future. Recently I had to hire two different freelancers. One sat in her

office moving symbols around. She transcribes tape-recorded interviews

and charges $25 per hour. The other is a guy who works out of his home

repairing greasy kitchen appliances. He charges $50 per hour, and as far

as I could tell had more business of the two. Krugman’s argument is

that these "manual crafts" (as they are bound to be labeled

when so high-priced) will level the salary discrepancies that now exist

between high tech and low tech occupations.

My argument is that great gardeners will be high-priced not

only because they are scarce and exceptions, but also because they, like

everyone else, will be using technology to eliminate as much of the

tedious repetitive work as possible, leaving them time to do what humans

are so good at: working with the irregular and unexpected.

At the dawn of the industrial age it would have been

difficult to imagine how such quintessential agrarian jobs as farming,

husbandry, and forestry could become so industrialized. But that is what

happened. Not just agrarian work, but just about every imaginable

occupation of that period—especially menial labor—was

intensely affected by industrialization. The trend was steady: The

entire economy eventually became subjected to the machine.

The full-scale trend toward the network economy is equally

hard to imagine, but its progression is steady. It follows a predictable

pattern. The first jobs to be absorbed by the network economy are new

jobs that could only exist in the new world: code hackers, cool hunters,

webmasters, and Wall Street quants. Next to succumb are occupations with

old goals that can be accomplished faster or better with new tools: real

estate brokers, scientists, insurance actuaries, wholesalers, and anyone

else who sits at a desk. Finally, the network economy engulfs all the

unlikely rest—the butchers, bakers, and candlestick

makers—until the entire economy is suffused by networked

knowledge.

The three great currents of the network economy: vast

globalization, steady dematerialization into knowledge, and deep,

ubiquitous networking—these three tides are washing over all

shores. Their encroachment is steady, and self-reinforcing. Their

combined effect can be rendered simply: The net wins.

Strategies

Maximize the value of the network. Feed the web first.

Networks are nurtured by making it as easy as possible to participate.

The more diverse the players in your network—competitors,

customers, associations, and critics—the better. Becoming a member

should be a breeze. You want to know who your customers are, but you

don’t want to make it hard for them to get to you (IDs, yes;

passwords, no). You want to make it easy for your competitors to join

too (all their customers could potentially be yours as well). Be open to

the power of network effects: Relationships are more powerful than

technical quality. Especially beware of the

"not-invented-here" syndrome. The surest sign of a great

network player is its willingness to let go of its own standard

(especially if it is "superior") and adopt someone’s

else’s to leverage the network’s effect.

Seek the highest common denominator. Because of the

laws of plentitude and increasing returns, the most valuable innovations

are not the ones with the highest performance, but the ones with the

highest performance on the widest basis—the "highest per

widest." Feeding the web first means ignoring state-of-the-art

advances, and choosing instead the highest common denominator—the

highest quality that is widely accepted. One practical reason to pick

the highest-per-widest techniques and technologies is because complex

technologies require passionate and informed users who can share

experience and context, and you want the maximum dispersion of usage

that doesn’t sacrifice quality.

Don’t invest in Esperanto. No matter how superior

another way of doing something is, it can’t displace an embedded

standard—like English. Avoid any scheme that requires the purchase

of brand new protocols when usable ones are widely adopted.

Apply an embedded standard in a new territory. Is

there a way to accomplish what you want using existing standards and

existing webs in a different context? Inventing a novel standard for an

existing network is quixotic. But some of the greatest success stories

in current times are about firms that master one network and then use

its embedded standards to exploit an established network in need of

improvement. This process is called "interfection." The

present revolution in telephony is all about zealous internet firms that

are interfecting the old Bell-head world of moving voices with newly

established protocols for moving data on the internet (known as internet

protocols, or IP). The huge increasing returns that spin off the

internet give them a great advantage. Indeed, one telephony standard

after another is falling before the relentless march of IP. Likewise,

aggressive companies are leveraging the established desktop standard of

Windows NT—with all its plentitude effects—to interfect new

domains such as telephone switching gear. Even the huge cable TV

networks have something to offer. The emerging standards for video

transmission, such as MPEG, are trying to migrate onto the internet. In

choosing which standard to back, consider dominant standards outside

your current network that could interfect your own turf.

Animate it. As the network economy unfolds, more firms

will begin to ask themselves this question: How do we put what we do

into the logic of networks? How do we prepare a product to behave with

network effects? How do we "netize" our product or service?

(The answer is not "put it on a web site.") Architects, for

instance, generate huge volumes of data. How can they be standardized?

How can the data about a physical object (say a door) flow through or

with that object? What are the fewest functions we can add to glass

windows to incorporate them into networks? What steps can a contractor

take to allow the networked flow of information from any architect to

any contractor to any builder to any client? How do we increase the

number of networks our service embraces?

Side with the net. Imagine that in 1960 an elf let you

in on a secret: For the next 50 years computers would shrink drastically

and cheapen yearly on a predictable basis. Subsequently, whenever you

needed to make a technological decision, if you had counted on the

smaller and cheaper, you would have always been right. Indeed you could

have performed financial miracles knowing little more than this rule.

Here is today’s secret: In the coming 50 years, the net will expand

and thicken yearly on a predictable basis—its value growing

exponentially as it embraces more members, and its costs of transactions

drop toward zero. Whenever you need to make a technological decision, if

you err on the side of choosing the more connected, the more open

system, the more widely linked standard, you will always be right.

Employ Evangelists. Economic webs are not alliances.

There are often few financial ties among members of a web. An effective

way of establishing standards and coordinating development is through

evangelists. These are not salespeople, nor executives. Their job is

simply to extend the web, to identify others with common interests and

then assist in bringing them together. In the early days when Apple was

a cocreator of the emerging PC web, it successfully employed evangelists

to find third-party vendors to make plug-in boards, or to develop

software for their machines. Go and do likewise.

continue...

|