Everything I Know about Self-Publishing

This essay is also available on my Substack. Subscribe here: https://kevinkelly.substack.com/

In my professional life, I’ve had several bestselling books published by New York publishers, as well as many other titles that sold modestly. I have also self-published a bunch of books, including one bestseller on Amazon and two massive hit Kickstarter-funded books. I have had lots of foreign edition books released by other publishers around the world, including bestsellers in those countries. Every year I also publish a few private books to give away. I’ve contracted books to be printed in the US and overseas. I’ve sold big coffee-table masterpieces and tiny text booklets. Together with partners, I run some notable newsletters, a very popular website, and a podcast with 420 episodes. I accumulated followers on various platforms. I’m often asked for advice about how to go about publishing today, with all its options, so here is everything I have learned about publishing and self-publishing so far.

The Traditional Route

The task: You create the material; then professionals edit, package, manufacture, distribute, promote, and sell the material. You make, they sell. At the appropriate time, you appear on a book store tour to great applause, to sign books and hear praise from fans. Also, the publishers will pay you even before you write your book. The advantages of this system are obvious: you spend your precious time creating, and all the rest of the chores will be done by people who are much better at those chores than you.

The downsides are also clear: Since the publisher controls the money, they control the edit, the title, the cover, the ads, the copyrights, and licenses. Your work becomes a community project, and it slows the whole process down, because yours is not the only project everyone is working on. Your work needs to fit into their lineup, their brand, their catalog, their pipeline, their schedule of all the other projects going on. The pace can seem glacial compared to the rest of the world.

For the most part, however, the peak of this traditional system is gone, finished, over. Reading habits have altered, buying habits are new, and attention has shifted to new media. It’s an entirely new publishing world. Today, some books experience some parts of this, but exceptionally few are treated to this full traditional process.

Publishers

Established mass-market publishers are failing, and they are merging to keep going. Traditional book publishers have lost their audience, which was bookstores, not readers. It’s very strange but New York book publishers do not have a database with the names and contacts of the people who buy their books. Instead, they sell to bookstores, which are disappearing. They have no direct contact with their readers; they don’t “own” their customers.

So when an author today pitches a book to an established publisher, the second question from the publishers after “what is the book about” is “do you have an audience?” Because they don’t have an audience. They need the author and creators to bring their own audiences. So, the number of followers an author has, and how engaged they are, becomes central to whether the publisher will be interested in your project.

Many of the key decisions in publishing today come down to whether you own your audience or not.

Agents

In the traditional realm, agents helped authors and they helped publishers. Publishers did not want to waste their time evaluating probable junk, so they would spend their limited time looking at what agents presented to them. In theory, the agent would know the editors’ preferences and know what they were interested in, and the editor could trust them to bring good stuff.

For the author, agents had the relationship with editors, would know who might be interested in their project, and the agent would guarantee that the legal contracts were favorable to the author, and most importantly, negotiate good terms. For this work, agents would take 15% off the top of any and all money coming from the publisher. For most authors, that is a significant amount of money.

Are agents worth it? In the beginning of a career, yes. They are a great way to connect with editors and publishers who might like your stuff, and for many publishers, this is the only realistic way to reach them. Are they worth it later? Probably, depending on the author. I do not enjoy negotiating, and I have found that an agent will ask for, demand, and get far more money than I would have myself, so I am fine with their cut. Are they essential? Can you make it in the traditional publishing world without an agent? Yes, but it is an uphill climb.

The problem is, how do you find a good agent? I don’t know. I inherited a great agent very early in my career from the publisher I first worked for, and I have happily been with them since. If I had to start from scratch now, I’d ask friends with agents who make stuff like my stuff to recommend theirs.

In self-publishing, you avoid agents and so keep that 15%.

Advances

What an agent will ask for from a publisher is a bunch of money upfront, when the contract is signed. This is the advance. You pitch a book, and if the editors accept it, they give you a deadline of a year or so to produce it. The role of the advance is to pay you a wage until the book is released, after which it will begin earning royalties for you. Royalties might be something like 7-10% of the retail price per book. The money you get on signing is technically an “advance against royalties.” Meaning that whatever they pay you in advance is deducted from your royalties, so you won’t be paid anything further beyond the advance until and unless the earnings of your royalties exceed the advance.

It is very common for authors to not earn anything beyond their advance. The calculation for the amount of the advance goes roughly like this: Let’s say you earn $1 royalty for every book sold. The publishers estimate they can sell 30,000 copies in the first year, and so they offer you an advance against future royalties of $30,000, or one year’s worth of sales. Obviously, many other factors go into this equation, but to a first approximation, the most you will get for an advance is based on what kind of sales they expect immediately.

The rule of thumb for an author is that you should get the biggest possible advance you can (and this is how an agent can help) – even if this means you won’t earn out the advance. The reason is: the bigger the advance, the bigger commitment the publisher must make in promotion, publicity, and sales. They now have significant skin in your game. Publishers are stretched thin, and their limited sales resources tend to go where they have the most to lose. If an advance is skimpy, so will be the resources allotted to that book.

BTW, you should not have concerns about taking a larger advance than you ever earn out, because a publisher will earn out your advance long before you do. They make more money per book than you do, so their earn-out threshold comes much earlier than the author’s.

Thus one of the advantages of this traditional system – of going with a publisher – is that they bankroll your project. They reduce a bit of your risk. Likewise, that is the genius of Kickstarter and other crowdfunders for self-publishing: the presales bankroll your project, reducing risk. Crowdfunding becomes the bank.

Crowdfunding

I’ve written a whole essay on my 1,000 True Fans idea, simplified as thus: You don’t need a million fans to make self-publishing, or the self-creation of anything, work. If you own control of your audience – that is if you have a direct relationship with your customers individually, having their names and emails, and can communicate with them directly — then it is possible to have as few as a thousand true fans support you. True fans are described as superfans who will buy anything and everything you produce. If you can produce enough to sell your true fans $100 per year, you can make a living with 1,000 true fans. I go into this approach in greater detail in my essay first published in 2008 which you can read here.

Today there are many tools and platforms that cater to developing and maintaining your own audience. In addition to crowdfunders such as Indiegogo, Kickstarter, Backerkit, and dozens more, there are also tools for sustaining support with patrons, such as Patreon. Crowdfunders tend to be used at the launch of a project, while something like Patreon permits constant support, primarily for a creator rather than a particular project. These can be combined, of course. You could launch your self-published work with a Kickstarter, and then gather Patreon support for sequels, backstory and making-of material, future editions, or side projects. Periodic publications have subscriptions for ongoing support.

These days backers expect a video — and other marketing bits – selling the book. Pre-sales for a crowdfunding campaign have become very sophisticated and require a lot of preparation. The Kickstarter for my Asia photobook was relatively simple and crude.

The chief advantages of crowdfunding are three, and they are significant: 1) You can get the funds before you create in order to support you while you create. 2) You keep all of the revenue (minus 3-5% for the platform), unlike an outside publisher. And 3) You own the audience, for future work.

The disadvantages are also three. 1) It is a huge amount of work. Most crowdsource campaigns go for 30 days and tending it for 30 days is a full-time job. 2) To be successful requires a different set of talents – marketing, sales, social engagement – other than what a creator may have. 3) You are responsible for making sure your fans actually get what they were promised. This “fulfillment” aspect of crowdfunding is often overlooked until the end, when it turns out to be the most difficult part of the process for many creators.

Production

Once upon a time, it was a huge deal to design and physically print a book (or press a music album, or deliver a reel of film). Today those processes can be done by amateurs with little experience. And often digital versions make creating, duplicating, and distribution even easier than ever.

There are three paths to production: traditional batch manufacturing; on-demand printing; digital publishing.

Batch Printing Presses

The traditional way of printing hardcover books still exists and it is a big business. A really first-rate printer will have different kinds of presses for different jobs – including the same fast digital printers as the on-demand printers. In fact, for some jobs, they will use these same digitally controlled ink-jet printers, just at a larger scale and speed. The chief advantages of classic printing on paper are three: you get scale, quality, color.

Pages from my first photobook, Asia Grace, published by Taschen, stacked up in their printing plant in Verona, Italy. In the old days before presses were completely computerized, the art director for the book (me) would be present during printing to oversee the many color tradeoffs each signature of pages needed.

Scale: Books printed in larger volume batches, or “runs,” can win huge discounts on the price per copy. A regular-sized hardcover book printed in Asia might only cost a few dollars to print, and a few more dollars for packing and shipping to your home. That’s a great deal if you list a book at $30. The higher the volume, the lower the price per unit. Printing outside of Asia is more expensive, but still worth considering – if you think you want a lot of copies, say more than 5,000 to start.

Quality: There is a resurgence in considering a well-crafted book as an art object. By leaning into its physicality – adding an embossed cover, heavy rag paper, deckled edges, glorious binding – the book can transcend its intangible counterpart on the Kindle. You as a publisher can make a book a unique custom size, or with magnificent die-cut covers for added zest and higher prices. Some self-published authors offer handsome bound book sets, or books hand-signed via tipped-in sheets, or super high-end limited editions, cradled in their own box. All these kinds of qualities require a collaborating printer somewhere.

Color: On-demand printing can do color, but not oversized, and not cheaply. In my experience, serious coffee-table visual books still need the hand-holding and economics of a printing plant. And I regret to say, that after many years of searching, I have not found a printer in the US capable of doing large full-color books at a reasonable price. You are most likely going to have to go to Asia, such as Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, India, or Turkey. China still has the best prices with the highest quality of color printing.

The disadvantages of having your book printed at a printer are #1: You have to house and store them somewhere. Either you have an available basement or garage, or you rent a place, or you hire a dropshipper, or you pay for a distribution giant like Ingram or Amazon to handle it for you. The full run of a book can take up more room than you might think when they are packaged up for shipping. My Vanishing Asia book set, financed on Kickstarter, printed in Turkey, filled up 4 shipping containers, each 40 feet long! That is a LOT of books to store.

Disadvantage #2 is that you need to pay the printer first, long before you sell the books. Not only is this a cash flow challenge, but you have to guess how many books you will sell before they are sold. (Having the pre-sale on a crowdfunding platform like Kickstarter is a big help in relieving that problem.) To get the best price you need to print a lot, but if you print a lot, you have a lot to pay for and to store if they should not sell.

On-demand

You can use free software to design your book and then send it to an on-demand printer to make 1 copy or 1,000 copies, printed one by one as each copy is sold. The copy does not exist till it is sold, so there are no books to bank, store, or ship. An on-demand regular softcover book would cost about $5 to make. It will be professional quality, indistinguishable from a trade book you might buy on Amazon, in part because many of the books from big-time publishers you buy on Amazon are actually printed on-demand using this same technology. (Big-time publishers are also printing on demand!) However, while the ink printing is first class, the bindings, paper quality, cover details won’t be up to what you can get with the best modern presses. What you’ll get is the good-enough printing contained within the average hardcover book.

The advantage to a creator (and to NY publishers) is that there is no inventory of unsold books to store or handle. You print the book when, and only when, it is sold. The disadvantage is that the cost of printing is more per book.

I can use four different services to print on-demand books. My preferred color and photo/art book printer is Blurb, for quality and ease of use. They keep up with the state-of-the-art color printing. You can design your book, export it as a PDF and have Blurb print it on-demand. Or you can use Blurb’s own web-based design program, or you can use a version of its software built into Adobe’s Lightroom, which is pretty standard for photographers. It’s very simple to go from photographs to a very designed book and then printed.

Sample pages from the various coffee table books I have had printed on demand from Blurb. Some of these books have editions of 2 copies; however the quality of the color printing is first class.

A second option for on-demand printing of standard books with black and white texts, as well as books with color illustration, is Lulu. Their photo/art books are a bit cheaper than Blurb. They are very competitive with standard text-based books. Most importantly, Lulu integrates with your own customer list, so you own your audience.

That is not true of the third option, which I also use a lot: Amazon. Amazon offers its print-on-demand service, called KDP, to anyone who wants it, with the added huge advantage that your book will be not only listed on Amazon immediately, but also delivered by Amazon’s magical logistical Prime operation. So potential fans can discover your work on Amazon and then have it delivered to them the next day for free. This is huge! But the huge and sometimes deal-killing disadvantage is that you do not know who your readers are, as you do with Lulu. Although Amazon makes it ridiculously easy to create and sell a book, with them you don’t own your audience. But in some cases, that is still worth it.

The fourth option is IngramSpark. I have little direct experience with this vendor, but others who do claim it is the best choice for text-based books aimed at libraries and bookstores. Indie bookstores are doing much better than chain bookstores and they usually avoid Amazon’s distribution system, Ingram is their main vendor for getting books — as it is for libraries. In addition to getting your book into the Ingram distribution, IngramSpark offers the self-publisher more options for book sizes, paper and binding.

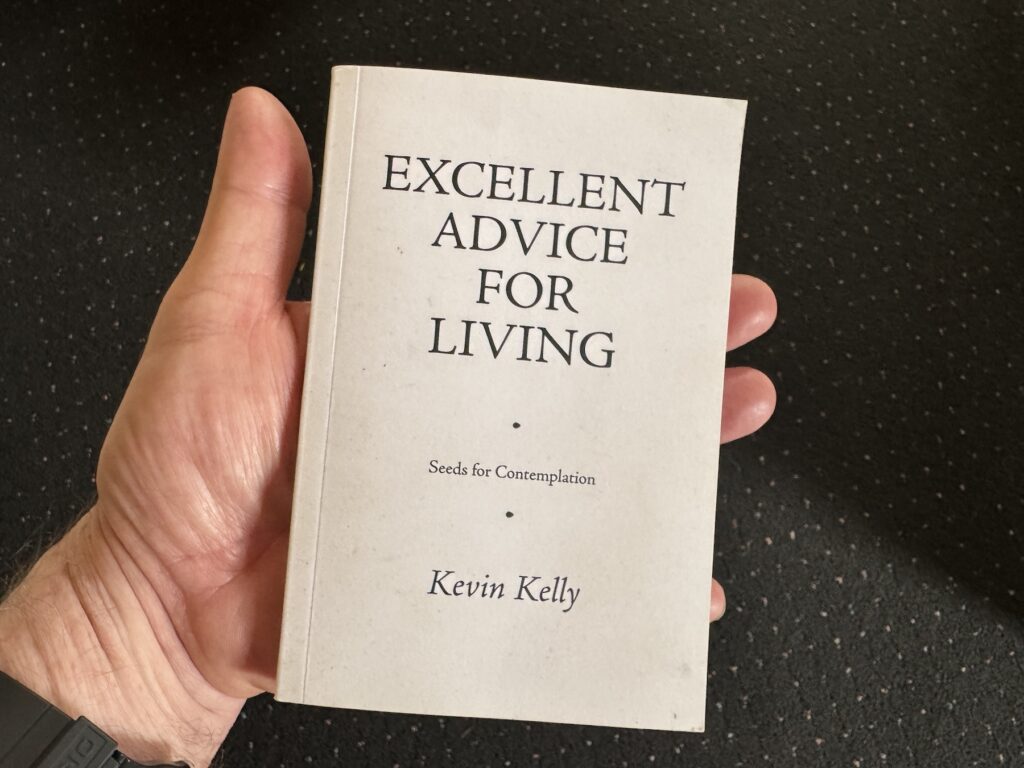

Because you can print as few as one copy of a book, I use these on-demand print services to manufacture prototype versions of a book to check for its sizing and feel. This small on-demand prototype of my book of advice was later published in a larger page size by Penguin/RandomHouse.

Digital

By far the easiest way to publish a book is to sell a digital copy of it. More authors should consider just publishing digital books. You still have to promote it, but you don’t have to print it, ship it, handle it, or store it. A commercial publisher might offer the author a royalty of 7% of the retail price which is say $2 per $30 book, so you may make just as much money per book selling it for $2 in digital. Creating digital books is a great way to start a publishing career. I have two friends who started publishing their science fiction stories as inexpensive digital short stories, which sold well, and then were later discovered by print publishers, made into printed books, and eventually turned into movies by Hollywood. And they still sell the digital versions!

You can sell an e-book – or even a chapter of a book – on Amazon’s KDP. You can easily make a book for the Kindle. I’ve had some digital books up on Amazon KDP for the past ten years, and they continue to sell slowly, yet I have not had to do anything with them since they were uploaded. While the Kindle gives you a royalty of 70%, and accesses a large Amazon/Kindle audience, its downsides are that you don’t own your audience, it demands exclusivity, and you must use their proprietary file format which removes any distinctive interior designs and prevents it from being read on other devices. There are dozens of other e-book readers and e-book platforms like Kobo, Apple Books, and Google Play Books who have different proprietary constraints. IngramSpark has an interesting hybrid program for e-book + on-demand printing.

These days a lot more people are comfortable reading a book in PDF form. I sell secure PDFs of some of my books on Gumroad, an easy-to-use web-based app, that collects the payment and sends the buyer an authorized copy. Gumroad works fine, does not charge much, and is super easy to set up; it is perfect for the low digital sales volumes I have.

The digital publishing world is fast-moving, and I don’t have as much recent experience with e-books to feel confident in finer resolution recommendations.

Audiobooks

Another important digital format I neglected to mention in the first version of this piece is Audiobooks. For the past decade audiobooks has been the fastest growing format for books — the one sunny spot in a worried landscape. There are many readers who only audit books, and never read them. I don’t have any experience in self-publishing audio books; all my mainstream publishers developed the audio versions with almost no input from me. But my friend and science fiction author Eliot Peper has self-published 9 audiobooks, sometimes hiring voice actors and, more recently, narrating them himself.

Currently the platform of choice for self-publishing audiobooks is ACX. ACX is a do-it-yourself platform, run by Audible, the major audiobook platform, and is also owned by Amazon. They are a full-service platform with sound quality tests, and a million narrators you could hire, and other tools to make the process easy. They take a hefty royalty of 40% and demand exclusivity, but your book is listed on Audible; for many readers that is the only place they will ever look for audiobooks. Alternatives such as Spotify are expanding into audiobooks which might make better deals with authors.

Distribution

Digital is easy, but increasingly, the “difficulties” of analog books have become an attraction. Some readers gravitate to the tactile pleasures of a well-made artifact and revel in the physical chore of turning pages. Sometimes the content of a book demands a bigger interface than a small screen can provide, so it needs the oversize release of a large printed page. Some appreciate the longevity of paper books, which never go obsolete and can be read for centuries without a power source or updates. Others are attracted to the serendipity of browsing a bookstore. And some folks value the limited scarcity of a printed volume.

But once words are printed on a page you have to ship them somehow. On-demand printers like Amazon KDP, Lulu or Blurb will directly ship the books to individual readers as they are ordered one by one. There is no inventory for you, and thus no work for the author. The ability of the on-demand publishers to handle long mailing lists varies and is a bit of work. Amazon has the best prices for shipping (zero) but the worst facility to mail to a list. They want readers to order from their own Amazon accounts; Amazon wants to control the audience. Blurb can only ship to customers who order on Blurb. Lulu lets you control your own fan list but charges a lot more to ship.

Cartons of my heavy oversized graphic novel, Silver Cord, pile up in my studio after being shipped in from China. I was unprepared for the chore of shipping the over sized books out to all the backers without damage.

Let’s say you want to go all in, you print the books yourself, and now you have to get them to your fans. Three options; From the printing plant, the books will be shipped by truck to either:

- Your garage. You purchase mailing envelopes or boxes and tape them up and mail them out. Plus: you can sign the books. Minus: tons of ongoing work, and not cheap to mail, even with Media Mail in the US. Shipping globally is a huge headache, and insanely expensive.

- A Drop Shipper, or what is today called a 3PL. For a fee, this kind of company will pick your book from your inventory in their warehouse, package it, and ship it out to your fan, or a bookstore. You give them either a mailing list or access to your orders on Shopify or Kickstarter. Plus: no grunt work, no inventory at home. Minus, not cheap either and they also charge a storage fee for holding your books, which could be there for years. Commercial dropshippers also favor large volume enterprises. I am currently trying out dropshipper eFulfillment that has low minimums and works with small-time operators like me.

- Amazon. You ship your books to an Amazon warehouse, and they fulfill the orders on Amazon as a third-party merchant. You would be selling books, just other merchants sell toasters or toys. Plus: they handle everything, and they offer readers free shipping. Minus: they only order the number of books they expect to sell easily, so there can be a lag until sales start, and of course, they only handle books bought on Amazon. That can be fine. I did one book that was only available on Amazon, nowhere else — I did not have any copies myself — and it sold great, with zero distribution worries on my side.

Promotion

The short version: it is not hard to produce a book. It is much harder to find the audience for it and deliver the book to them. At least 50% of your energy will be devoted to selling the book. This is true whether you publish or self-publish.

A misconception about Kickstarter, Backerkit, and crowdfunding platforms like Patreon is to imagine that you will automatically find your audience there. It is almost the opposite. You won’t be able to have a successful crowdfunding campaign unless you bring the crowd with you. You must cultivate your audience BEFORE you ignite them on Kickstarter.

You won’t have time to build your audience during the fundraising period. The typical crowdfunding campaign lasts 30 days; that will be just long enough to entice them about your work. That also means that for a month, it will be a full-time job for somebody to promote, advertise, and “convert” your audience to your book or project. That somebody is probably you. These days promotion includes making a short video announcing the launch, devising tiers of “rewards,” keeping up with status notifications of how the campaign is going, and doing everything else you can to promote it to new fans. If there is no one willing or capable to give it a month, the effort will probably not reach your goals.

Because Kickstarter, Backerkit, IndieGoGo, Patreon, and other crowdfunders are a platform, there WILL be some people who discover your project there via referrals of similar projects – which is always a plus – but your dominant source will be the audience you accumulated earlier and brought with you. If your project has a likeable presence, the platforms can boost the awareness of it if you are lucky, so getting listed on the front page is something to aim for and it does help.

By now there is also a small industry of “growth” companies who plug into Kickstarter and kin, and who will help you run a crowdfunding campaign for a fee. I actually found that at least one of them was worth the fees they charged, which are now a 20% cut of the additional backers they bring in. They were able to enlarge my campaign way beyond my circle of friends and my existing 1,000 true fans. If I were doing a crowdfunder for the first time, I’d use a growth company like Jellop and I would partner with them from the very beginning.

Getting published by a New York publisher doesn’t get you off the hook. Even if you were to be published by a commercial publisher, you should expect to do serious promotion over the span of a month or more. In theory, the publisher would set up, or at least guide you, through the promotion, but that rarely happens anymore. Even with a commercial publisher releasing your work, you will end up doing the majority of whatever promotion gets done. As in, planning, coordinating, executing, and even paying for book tours and the like. You will be the publicity department no matter what.

Traditionally the promotion of a new book entailed a book tour for the author visiting larger bookstores, where crowds of fans would purchase books. Plus some advertisements for the book in magazines and newspapers, which would also review said book. Ideally this launch would also include appearances on TV talk shows, and maybe radio. None of this works anymore. There are no more paid book tours. Few, if any, book reviews in newspaper or magazines, or author appearances on TV. Fewer ads for books. If any of these do happen, they will be arranged and paid for by the author.

But because books tours have sort of disappeared, an enterprising author with an audience can arrange their own tour using their fan list. Many people crave a deeper connection to people they follow digitally, and these fans can fill a room. Recently Craig Mod, an unknown new author in bookland, arranged and paid for his own sell-out tour, astounding booksellers around the US who did not have enough of his books to sell (who is this guy?).

Instead, promotion for books have shifted online. There is booktok, where fans read new and favorite books for viewers on social media. There are podcasts, where authors can be interviewed at length. In fact, for my last two books – which basically got no reviews in publications – sold extremely well because I heavily promoted them on podcasts, big and small. I said yes to every podcast request who had more than 3 episodes. Even a small podcast audience is larger than the audience in most bookstores. And because podcasts can be niche and intimate, unlike say an appearance on TV, they sell books.

The rule of thumb in publishing is that how well a book sells in its first two weeks determines whether it is a bestseller or not. You want to concentrate most of the sales as pre-sales – either on a crowdfunding platform, or on your own, or as pre-sales for a publisher. One way or another this promotion job will be your job, and can end up being at least half of your total effort on a book.

Non-book publishing

Creating a book has become so easy, that most books these days should probably not be a book. Not every idea — or story — needs the long format of a book. In fact, few do. Instead, they should be a magazine article, a blog post, an op-ed, or a newsletter.

Subscriptions

While we have been long trained to pay for books, we have less of a habit of paying for shorter material, particularly in digital form. Printed magazines and newspapers are disappearing, and few survived the transition to full digital, so there are fewer and fewer opportunities to get paid for publishing your work in a form other than a book. Blogs were great, but for a long time, there was no way to get paid, so they were a non-starter for many authors. Recently platforms for paid newsletters, like Substack, Ghost, Beehiiv, Buttondown and so on have risen, creating a small ecosystem for professional writers.

Substack in particular has done a great job in educating the audience to expect to pay for quality content. All the platforms promote subscriptions as the revenue model, instead of ads. A typical subscription newsletter will start charging $10 per month, although you can charge as much or as little as you want, including free. (Reminder that $10 per month is more than $100 per year, so you could do quite well with 1,000 true fans.)

You don’t need Substack, or any of the other platforms to publish a newsletter for money. If you have an audience you can publish your own with some easy software apps. Well-known Mailchimp does lists easily, but not payments. Memberful has a digital payment function and customer management tools; but you have to host the content, and shape your newsletter. It’s great for building your own custom publication, with full ownership of the audience and the design. Substack, Ghost and others make it easy for beginners to build their own subscription newsletters. Medium is another similar, but different, online publishing platform. They host many writers from many backgrounds, but readers pay only one fee to Medium, which Medium then funnels to the writers and editors who curate this mega-magazine. I don’t have enough experience with it as a writer to know how viable it is. I’ve written there but I get no access to the audience directly.

Unmonetised publishing

That’s also part of the challenge of a blog; no ownership. Blogging on your own website is extremely powerful. There are zero gatekeepers. Publishing is instant. Mostly free. You can say anything you want. You can write a little or a lot, every day or once a year. You have 100% control of the design. In many ways, it is the ultimate publishing platform. It’s a fantastic home for great writing and new ideas. For a while blogs had their heyday. But blog websites have three significant downsides which temper their supremacy. One, fewer and fewer people are going directly to a website on a regular basis; it’s harder to maintain an audience and very hard to grow one on the web. Two, unless you implement a membership level of some sort, you actually don’t own your audience. Readers are anonymous. Sometimes you can implement comments on a blog, but they need to be managed and vetted, and their IDs are not useful for an author. And three, blogs, almost by definition, are open to all visitors and don’t have significant revenue models. The fact that you can not easily charge for the writing you do on a blog has been the reason why Substack and other subscription platforms arose. (There is currently a few blogs like Kottke, which are experimenting with paid membership to comment, while keeping the blog open and free.)

In the same vein, X(Twitter), Instagram, TikTok and Facebook are bonafide real publishing platforms. In fact I have published the most significant parts from every page of one of my books, and every sentence of another book, on these social media. You can do serial publishing. But there is no revenue model. You can gain followers but not dollars. Sometimes followers can be transferred into a real audience that you have access to, but it is not easy, and certainly not automatic. While YouTube (see below) can fully support creators, I have not met anyone who is making money selling their content on the social media platforms.

Nonetheless, I continue to blog and to post on the socials; it’s the first place my writing goes. And sometimes, this diffuse audience is all that the writing needs.

Another advantage of the subscriber newsletter platforms like Substack and Ghost, et al, is that there is a social component, and they can be a great way to build a community around your writing. They make it very easy for readers to comment. They also have built-in analytics that can help you understand your audience and how they engage with your content. Equally important, their systems recommend other newsletters to current or new subscribers, thereby enabling others to discover your work. This network effect can help you find and grow your audience. Once a reader has an account for one newsletter, it is very easy for them to sign up for another newsletter from another author.

The design and layout on these platforms are currently very limited, and work best for publishing primarily text, but the platforms are also moving into video and images.

You could think of a newsletter as a subscription to an ongoing book. Writing a book “out loud” — publishing it in parts as you write it — has become much more common. You write in shorter sections, publish the chapters immediately online, and then solicit feedback. This works in both fiction and non-fiction. In fiction, you can publish chapter books, serially, one chapter at a time. In non-fiction, you can write essays or blog posts or newsletter issues (see above), and then make edits to the material later based on comments and corrections. The text is essentially “proofed” and fact-checked by the earlier readers. I have written several books this way, and this process increased the quality of the material manyfold. In addition to correcting some embarrassing mistakes, it also bettered some parts with alerts to ideas I was not aware of.

In the old days, mainstream publishers actively tried to prevent authors from publishing material beforehand, but now the speed of correction, the ease of comments, and the ease of pointing to overlooked research is so easy for readers to do, that it makes great sense to rehearse your writing in public. You can also look at this dynamic process of write > publish > rewrite > republish as a way of building up and maintaining attention. In general, people devote less time to books because of the huge amount of attention they require. It is easier to string that attention out in an ongoing series of posts. If a long-form book comes out of it, it is much easier to reel that string of attention back into the book. And with the advent of paid subscriptions, readers can subscribe to your ongoing book.

Screening

We used to be people of the book, but now we are people of the screen. Our culture used to be grounded on scriptures, constitutions, laws, and canon — all written texts. These were fixed in immutable black and white marks on enduring paper, written by authors, from whom we got “authorities.” Now our culture pivots on screens, which are fluid, mutable, flowing, liquid, and fleeting. There are no authorities. You have to assemble the truth yourself. Books no longer have the gravitas they did, and my children and their friends are not reading many of them. Instead, they watch screens. They read the text in moving images. They are learning more from YouTube than books in school.

While books will continue to be published, the center of attention has shifted to moving images. Worldwide the number of hours of attention given to screens dwarfs anything given to pages. Today, to seriously talk about publishing we must talk about video, VR, reels, movies, games, YouTube, TikTok, and of course AI. The audiences for my books are counted in thousands but the audience for my TED talk videos are counted in millions. I spent minutes preparing for my TED talks and years preparing my books, but given the asymmetry of attention and influence, I should have reversed my own attention and given my videos years of work and then only hours creating the book derived from it.

I don’t have enough personal experience in this emerging media to offer useful advice right now; it may have to wait for part two. I do have a small group of friends who make their living publishing on YouTube and TikTok and Instagram. The screen is their prime media for non-fiction work. I know enough of these new kinds of professional creators to see that this mode is a very viable path. I also have sufficient evidence from my own platform tracking to clearly see that the audience for text is stagnant, and skews older, while the audience for moving images continues to expand greatly, while getting younger. Of the two, I know where I want to work. (It is not lost on me that this essay is text and not a video. I’m working on it….)

Summary Advice:

In conclusion, the way I approach publishing today is with as much self-publishing as I can handle. I’d write in public installments, as a subscription newsletter, or e-book single chapters, or simple posts on my blog. If I could find an audience that wanted more of the material, I’d rewrite, re-edit, re-compose the material into a longer form. I’d release that as an ebook, and/or on-demand printed book sold in my shopify shop. If the material was deep, or involved more creators than just myself, I’d consider crowdfunding it. Those presales allow me to target exactly how many copies to produce. I’d calculate the cost of drop shipping. And at every stage I’d be making some kind of visual version for YouTube and the other attention seeking channels, because that is where the attention is.

To clarify this complicated advice even further, I have made a flow chart of possible options for publishing and self-publishing. This is roughly the decision tree I tend to follow when I am figuring out the best mode for the material and my goals. I hope you find it useful too.

A 16-page PDF of this article is available for free download here.