The Information

I interviewed James Gleick in Wired this month about his new book. Here are some excerpts from the piece. Following them are a few extra unpublished bits from the interview.

Information flows everywhere, through wires and genes, through brain cells and quarks. But while it may appear ubiquitous to us now, until recently we had no awareness of what information was or how it worked. In his new book, The Information, science writer James Gleick documents the rising role of information in our lives and the way new technologies continue to increase its velocity, volume, and importance.

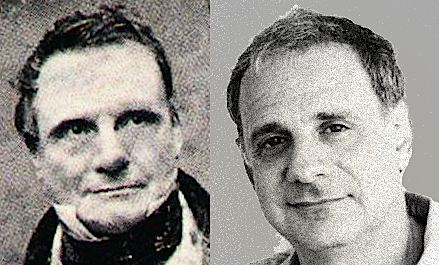

Charles Babbage and James Gleick. Separated at birth?

Kelly: I like your story of Charles Babbage, who in the 1820s basically invented the concept of computer a century before anyone, including him, could make one.

Gleick: Babbage was a man out of his time. People back then didn’t get what he was about. He was a mathematician, but he was engineering this machine that could be programmed. He was also obsessed with lock-picking, and the schedule of railroad trains, and cryptography.

Kelly: He was the prototypical hacker!

Gleick: Yeah, today there are many people who share these same preoccupations. And we’re aware of what they all have in common: information.

Kelly: According to your book, information underpins everything.

Gleick: Modern physics has begun to think of the bit–this binary choice–as the ultimate fundamental particle. John Wheeler summarized the idea as “it-from-bit.” By that he meant that the basis of the physical universe–the “it” of an atom or subatomic particle–is not matter, nor energy, but a bit of information.

Kelly: That sounds almost spiritual–that the material world is really immaterial.

Gleick: I know it sounds magical, but it needs to be understood properly. Information has a material basis. It has to be carried by something.

Kelly: The extreme view would be that all these bits that make up atoms are running on a very big computer called the universe, an idea first espoused by Babbage.

Gleick: That makes sense as long as this metaphor does not diminish our sense of what the universe is but expands our sense of what a computer is.

Kelly: But as you note, some scientists say that this is not a metaphor: The universe we know is only information.

Gleick: I’m not a physicist, but that concept resonates with something that we all recognize: Information is the thing that we care most about. The more we understand the role that information plays in our world, the more skillful citizens we will be.

The following did not appear in the published Wired interview for space reasons. They also may not have been generally interesting. But the conversation focuses on my current obsession of screen publishing so I’m running them here:

K: You are a bit unusual among journalists because you not only report on news, but you make news. In the early 1990s you switched from writing about information to starting an internet access company, Pipeline. [Profiled in Wired.] You moved from pushing a few bits on paper to pushing massive bits on wires. What did you learn from that experience?

G: In 1993, two years after I discovered email, I started this company to sell email access to the public. I did it because I wanted cheap Internet access, and it suddenly felt as though everybody around me did too. It was very thrilling being right in the middle of this cauldron at that great moment in history. I have no regrets, but I was constantly thinking, I need to find a real businessman to run this company. I need to get back to writing books. Although I made some money, it turned out that starting my own company was not necessary. I could’ve just waited.

K: These days you are dabbling in developing ebook and iPad versions of some of your previous books. It feels a little bit like 1993 again, when authors just can’t wait till the publishers figure out how to do digital publishing, so they plunge ahead by developing their own. Do you think you should just wait?

G: Yeah, it’s a tough problem for authors, because publishers belatedly woke up to the potential of ebooks and are now demanding control over the ebook rights. But I believe, and the Authors Guild believes, that if the rights are not specifically and clearly reserved by the publisher, then they’re the authors’. I think authors should find ways to exploit these rights and get their books into these formats.

K: Do you think your next book will be in paper?

G: Yes, I do. But not exclusively. I’m already reading more on devices than I ever did, but I think books are books in whatever medium.

K: As someone who earns his living writing books, do you think you’ll survive as the price of electronic books head towards three dollars a book?

G: As nervous as publishers have been about ebooks, they’re making a lot of money from them. Ebooks are very lucrative because they are charging customers too much for them, and shortsightedly they are paying too little to authors. I think the market will force publishers to pay authors a little bit more and to charge less but the good publishers will still be able to make money.

K: You were heavily involved with the Authors Guild in suing Google to halt its Google Books program as first presented five years ago.

G: I believe now exactly what I believed and said then, which is that it’s great that Google’s doing this. They’re creating a very useful thing for the world. But to the extent that they’re profiting from the copyrighted works of authors they should be sharing the profits with the rights holders. In the settlement agreement with Google these issues were resolved, but as you know the agreement’s approval by Judge Chen is still up in the air. If he approves the settlement as is that would be great for everybody. Many books that are now only slightly visible online will become completely visible. And Google will make more money, and to the extent that they make more money, the rights holders will share in the profit as is reasonable and proper.