Ultralight Hiking

Tools for Possibilities: issue no. 94

Once a week we’ll send out a page from Cool Tools: A Catalog of Possibilities. The tools might be outdated or obsolete, and the links to them may or may not work. We present these vintage recommendations as is because the possibilities they inspire are new. Sign up here to get Tools for Possibilities a week early in your inbox.

Super ultra-lightweight camping

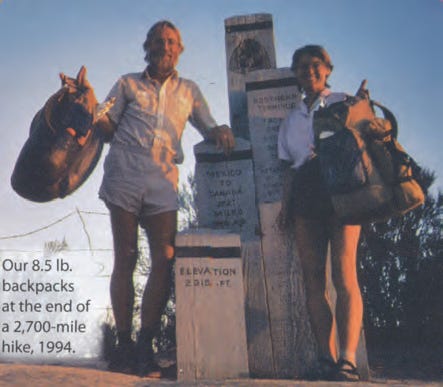

The joy of hiking is inversely proportional to the weight of your pack. Carry nothing and your pleasure is unbounded. No one has articulated the benefits and the know-how of carrying little as Ray Jardine. He can show you how to liberate yourself from your tent, water-filter, stove, and most of the rest of your gear. He also has the best tricks for completing long through-hikes. The best times I’ve ever had in my decades of trekking have been when I was carrying little more than what I was wearing, and hiking the way Jardine preaches. —KK

- Compare one of my packs – weighing 13 ounces and costing $10.40 to make – to a store-bought backpack weighing 7 pounds and costing $275.00. My pack is 12% of the weight and 4% of the cost.

I should point out, too, that the majority of nights we hikers spend in the backcountry are mild. We are not automatically going to encounter the ultimate storm the minute we step out the back door with lighter-weight gear. But should it happen, a properly pitched tarp will handle it. Pitching a tarp is not difficult, but the method differs from that of pitching a tent. The best way to make the transition from tent to tarp is to carry both on a few short outings. Pitch the tarp and sleep under it, and keep the tent packed in its stowbag and close at hand, just in case.

The reaction of these backpackers was typical of the many we met that summer. On paper, our lighter-weight methods may seem “radical” and idealistic. But when these people saw how easily we were doubling and sometimes even tripling their daily mileages, they tended to become less skeptical. The irony was that we were exerting ourselves no more than the backpackers. We were using our energy mainly for forward progress, rather than for load hauling. I see mileage as an effect rather than a cause. Not something to be struggled for, but merely a by-product of a more efficient style. My main focus is on the natural world, my place in it, and how that relates to the joys and the lessons learned along the way. I also find that when we reduce our barriers — our detachment — from the natural world, we stand to better our wilderness connection.

According to conventional backpacking wisdom, giardia contaminates all wilderness water, and we hikers and campers need to purify every drop that we drink; as well as what we use for cooking and brushing teeth. You can read this in hundreds of magazine articles and books. Jenny and I followed this rule faithfully during our first four mega-hikes. And I was sick with giardia-type symptoms many times.

Obviously, something was wrong. If we were being meticulous about filtering our water, then why was I not staying healthy? Jenny remained healthy, and she was drinking the same treated waster as I. Apparently my immunities were lower than hers. But the fact remains that somehow I seemed to be contracting parasites despite the assiduous use of the water filter. The filter cartridges we were using were common, brand-name varieties, and we had no reason to suspect they were not working properly.

Clearly, the conventional wisdom was not working. So we abandoned it and tried a different approach. While training for our fifth thru-hike we drank directly from clean, natural sources, a few sips at first, then gradually increasing in quantity over the weeks and months. In this way we helped condition our bodies to the water’s natural flora. Then during the actual journey we drank all our water straight from the springs, creeks and sometimes the lakes – after carefully appraising each source. And for the first time in years I remained symptom-free; and Jenny stayed healthy also — I doubt whether my illness had anything to do with the filtration or lack thereof. Rather, it had to do with the nature of the water sources we were using. During the initial journeys we were collecting from all but the worst sources, and treating it. In several cases that I can think of, I feel that this treatment — or any other available treatment — was incapable of making that water safe to drink. This is why, on that fifth trek, we collected water only from clean sources. Based on these experiments and their successful outcome, the following are my recommendations: Learn to recognize pristine water, and treat it if you prefer. Learn to recognize water that could be microbially contaminated, if only mildly, and treat it thoroughly. And most importantly, learn to recognize water that is beyond treatment, despite any reasonable degree of clarity. Such water can be extremely virulent, and no water treatment system available to hikers is capable of making that water safe to drink. Do not filter, boil or add purification chemicals to this polluted water. Do not use it for cooking or bathing. In the next section we will learn how to recognize such highly contaminated water.

Stealth camping. If you can manage to camp away from the water sources, and from the established campsites, then the many wonderful advantages of stealth camping will be yours. Stealth camping is a cleaner, warmer and quieter way to camp, and it offers a much better connection with nature. In all likelihood no one has camped at your impromptu stealth-site before, and the ground will be pristine. Its thick, natural cushioning of the forest materials will still be in place, making for comfortable bedding without the use of a heavy inflatable mattress. There will be no desiccated stock manure to rise as dust and infiltrate your lungs, nor any scatter of unsightly litter and stench of human waste. The stealth-site will not be trampled and dished; any rainwater will soak into the ground or run off it, rather than collect and flood your shelter. Bears scrounging for human food will be busy at the water-side campsites, and will almost invariably ignore the far-removed and unproductive woods. Far from the water sources you will encounter fewer flying insects, particularly upon the more breezy slopes and ridges. Above the katabatic zones the night air will be markedly warmer. And you can rest assured that your chances of being bothered by other people will be slim.

The drift box. On our longer hikes, Jenny and I often use what we refer to as a “drift box,” or “running resupply box.” This is a small parcel that we send ahead rather than home. It contains items that will probably be needed later, but not presently. These might include spare shoes and fresh insoles, extra socks, a spare water filter cartridge, an extra camera battery, a small whetstone, a utility knife with disposable blades, a tube of seam-sealing compound, a spare spoon, an extra sweater, and a roll of boxing tape. The drift box gives us occasional access to these items without having to carry them. We send it First Class to a station approximately two weeks ahead.

- Most large backpacks on the market weigh from five to seven pounds, and more. Yet the pack adds nothing to the journey, other than acting as the container for the equipment, clothing and food. To me, it makes no sense that the container should be the heaviest article of gear.

- This is because the gear needed for camping one night in the wilds is about what is needed for camping a hundred nights. The same holds true for the clothing, rainwear, and so forth. The only real variation is the supply of food.

- Where to fordAs a general rule, if the river is swift and knee deep or deeper, we do not attempt a wade. Rather, we scout the bank for a natural bridge. We have hiked as much as five miles along a creek in search of a safe crossing.

- If we find a place that appears safe to wade, but where whitewater lurks immediately downstream, we do not risk it. One slip, and the current could sweep a person quickly into the rapids.

- Also, if the creek is swift and its bed is solid rock, as with many places in the High Sierra, we look elsewhere. In all likelihood that riverbed has been polished by grit and coated with a translucent layer of algae that can be unimaginably slippery.

- Another technique that can help extend the miles is to use waypoints as springboards. Shelters, creek crossings, lakes, and trail junctions can serve to urge us several more miles. But the temptation might be to say to ourselves, “four more miles to Green Lake Shelter; I think we will stop there for the night.” This is letting the waypoint dictate progress. Instead, we could say to ourselves: “once we reach the Green Lake Shelter, we will continue for one more hour before makingcamp.” The idea is to use the waypoints as incentives, rather than as destinations.

Going light by going fast

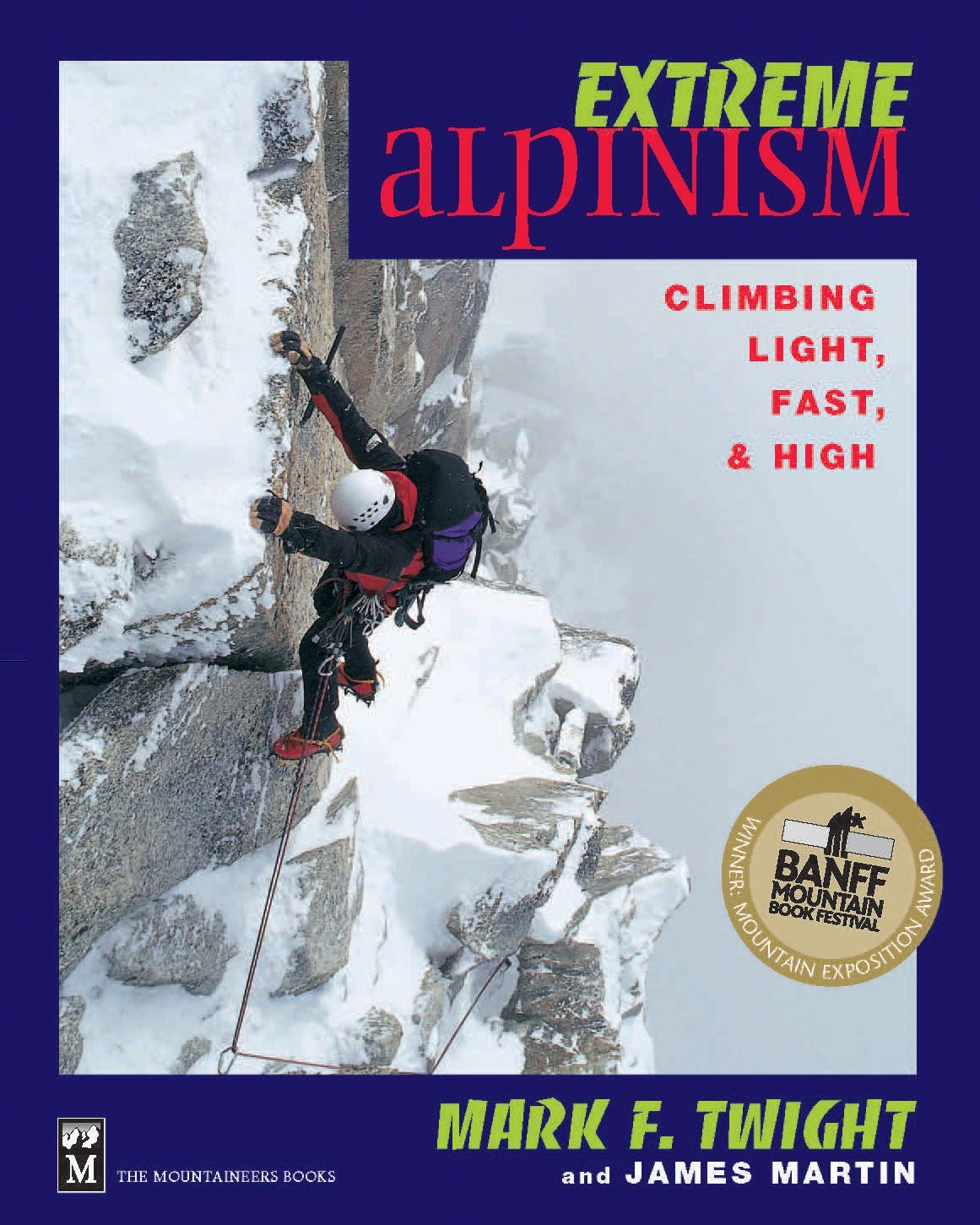

I’m struck by any book on a dangerous subject that looks as though it escaped the inspection of lawyers.Extreme Alpinism (with the exception of the title) is the best book I have read on any outdoor subject. It’s devoted largely to author Twight’s theory and practice of alpinism — his drastic gear weight reduction methods go far beyond simple ultralight camping. Twight has combined new ways of using clothing, equipment, nutrition, and training to survive impossible situations and achieve incredible feats. The sections on Twight’s own failures are a rarity and probably the best part. While I’m not an alpinist myself, this book has been inspirational in all my outdoor activities. — Alexander Rose

- Extreme alpinism can mean different things to different climbers. In this book, we define it simply as alpine climbing near one’s limits. We use “extreme” to denote severe, intense, and having serious consequences. To survive in the dangerous environment where ability and difficulty intersect, the climber must visualize the goal and the means to realize it. After training and preparation, the climber tackles the route, moving as swiftly as possible with the least equipment required. For a fully trained and prepared athlete at the top of his or her game, only the hardest routes in the world offer sufficient challenges to qualify as extreme.

- We look upon both the preparation for climbing and climbing itself as a process of self-transformation, of character building. Character means more than strength or skill. We will belabor this notion because it is the core truth at the heart of hard climbing. Extreme alpinism is a matter of will. We all know this to be true. In every endeavor, people who concentrate and refuse to quit become the elite.

An alpinist needs to acquire facility in rock climbing, ice climbing, weather forecasting, snow safety, approach methods, retreat techniques, bivouacking, energy efficiency, nutrition, strategy and tactics, equipment use, winter survival, navigation, and so forth. The more you know, the safer and more efficient you will be in the mountains.

In a dangerous environment, speed is safety. Climbing routes at the edge of the possible is akin to playing Russian roulette. Each time the cylinder spins, the chance of firing a live cartridge increases. Therefore, “Keep moving” is the mantra of the extreme climber. The idea of speed permeates this book. - It’s impossible to stay fully hydrated while actually climbing, so rehydrating at the end of the day or during breaks between hard effort is essential. Because of the climbing, your body will be dehydrated, your stomach and your entire system will be highly acidic, your muscles will be holding onto metabolic waste, and your glycogen reserves will be gone. First and foremost, you must drink. Plain water is fine. Once you are a quart ahead, start adding your recovery foods and supplements. Avoid acidic food and drink. Your body already is in an acid state, so look for foods that buffer it. Acidic foods also are more difficult to absorb. Citrus juices, for example, are acidic and the high sugar content will impede gastric emptying.

- Light and fast as a style results in the ultimate autonomy and self-determination — but any time you decide to pare food, fuel, and gear down to a marginal level, you accept great risk and must therefore accept great responsibility. If your style is too light, or you drop a crucial piece of gear, or the weather turns bad, you must retreat. Or if you are too high on the mountain, then you have to fail upward as quickly as possible. You must keep moving at all costs. Movement is your only safe haven.

- On the other hand, there may be no way in hell to do the route without sleeping on it. If that’s the case, live with the minimum. Do not pursue comfort. Aim for success only. On a one-bivy route, don’t plan on a good night’s sleep. Never take a cup and a bowl. The water bottle and the pan for the stove will do. Each climber may carry a spoon — that’s it. Forget your manners. Forget the Ten Essentials. No matter how long the intended route, carry only the genuinely essential.