Bird Behavior

Tools for Possibilities: issue no. 100

Once a week we’ll send out a page from Cool Tools: A Catalog of Possibilities. The tools might be outdated or obsolete, and the links to them may or may not work. We present these vintage recommendations as is because the possibilities they inspire are new. Sign up here to get Tools for Possibilities a week early in your inbox.

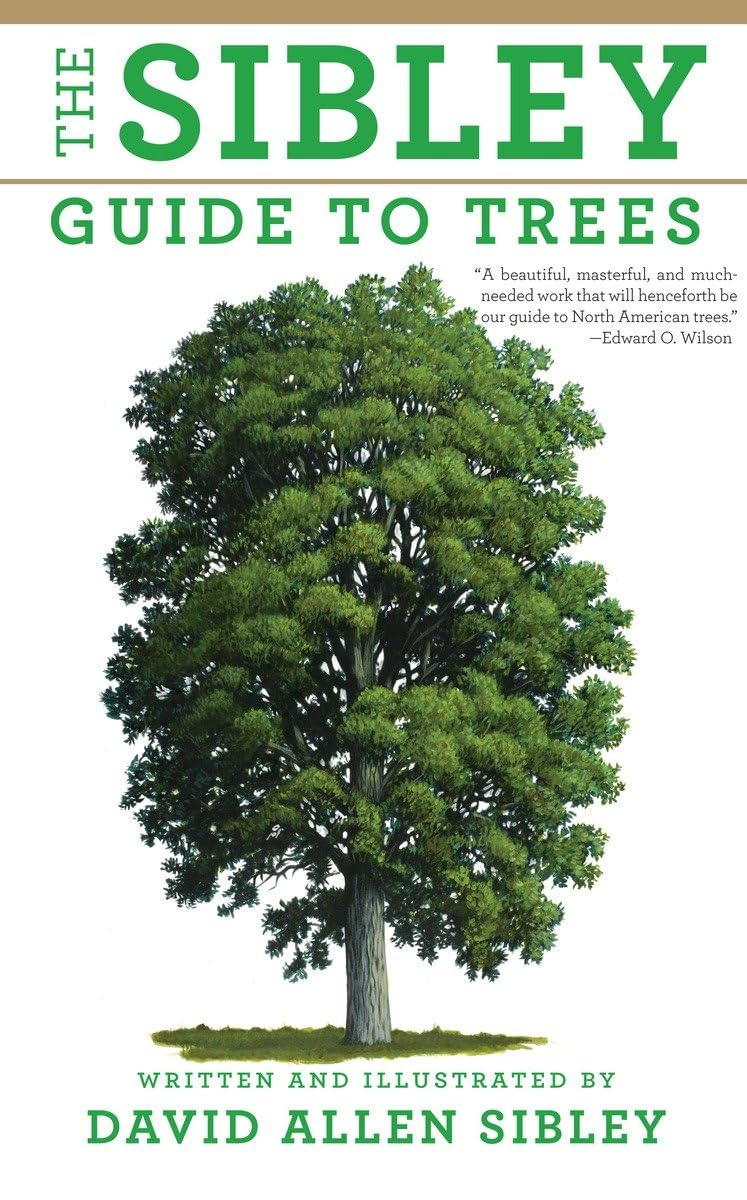

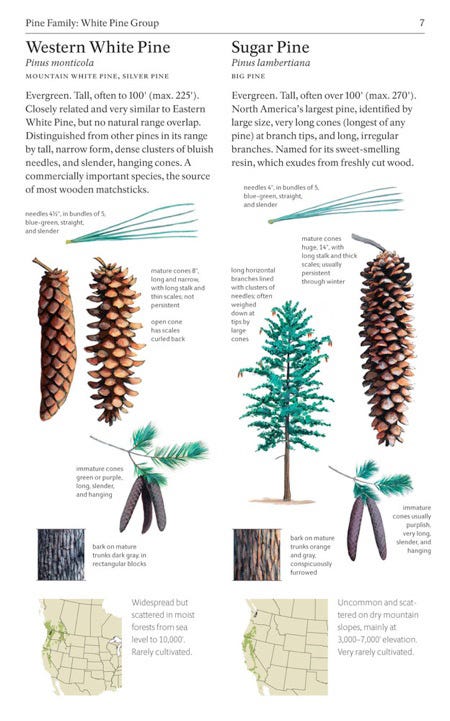

Best tree guide

Naturalist David Sibley, like Tory Peterson before him, made his reputation painting and annotating birds before expanding to other biological realms. Sibley’s guides to birds and bird behavior (recommended this page) are the best all-around guides to the birds of North America. Sibley’s beats out Peterson’s, and the dozens of others published today. Sibley’s newest book, also written and illustrated by him, is the best all-around guide to the trees of North America, again displacing the many other field guides to trees in print.

Sibley’s illustrations are clear, crisp, and accurate. He manages to maintain distinctions in tree types where species get fuzzy, like in the oaks, or firs. His maps are specific. He includes more parts of the tree than most guides — buds, bark, branches, seeds, silhouettes, flowers, cones, etc. — which really help in identification. And he includes not only native trees but many feral varieties, and even widely planted ornamentals. One detail I appreciate: he lists alternative common names to trees, since trees seem to have local names.

With Sibley’s guide I’ve been able to identify more trees than with other guides. However the book is big, not at all pocketable, or the kind of thing you are likely to take with you into the field on a hike. Perhaps future editions might remedy this. I use this quality softcover edition (a delight to browse) by taking samples and photos outside and returning home to identify. — KK

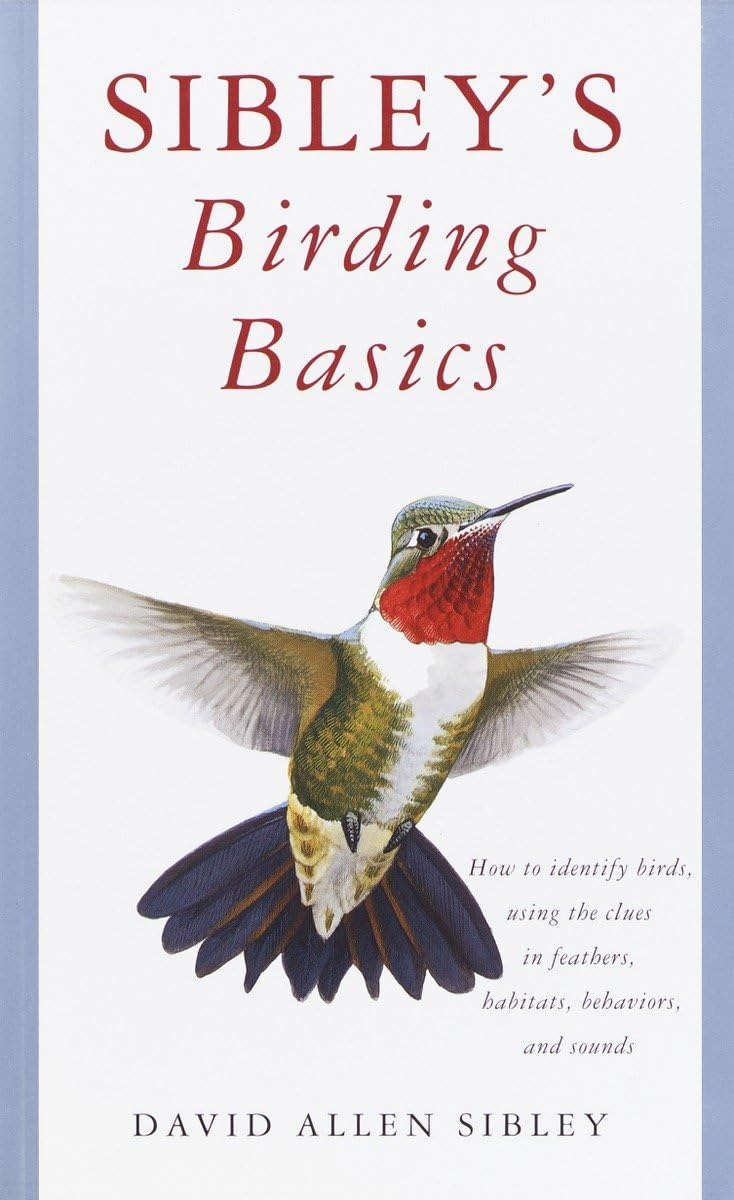

How to see birds

Our contemporary Audubon, David Sibley, will mentor you in how to see birds. This is not one of his legendary field guides; instead it’s a masterful course on how birds work, distilled into a small compact book, and illustrated with his impeccable drawings. Even if you’ve been birding all your life, every page will illuminate the art of seeing them. How can you tell just from a flitting glance in the dark that was a white-throated sparrow? Sibley the grand master tells how he does it. It will be a very long time before anyone else understands and communicates this hard-won knowledge better. —KK

Western Sandpiper in fresh (left) and worn (right) alternate plumage, with representative scapular feathers from each, showing the striking changes that take place gradually, over a period of about four months, with no molt. Most field guides can show only one example of each plumage, so they illustrate an “average” bird, somewhere between these extremes.

- The making of hissing, shushing, and squeaking noises (known among birders as “pishing”) is done in imitation of the scolding calls of certain small songbirds. It is often combined with imitations of the calls of a small owl in order to simulate the sound of an owl that has been discovered by songbirds. Birds approach to see what’s going on and to join in scolding the predator. Pishing is most effective when you are somewhat concealed within vegetation. The birds need to be able to get close to you without leaving their cover, and ideally there should be an open spot for them to sit when they do reach you. Curiosity will bring the birds in and then draw them to a perch where they can take a clear look at you.

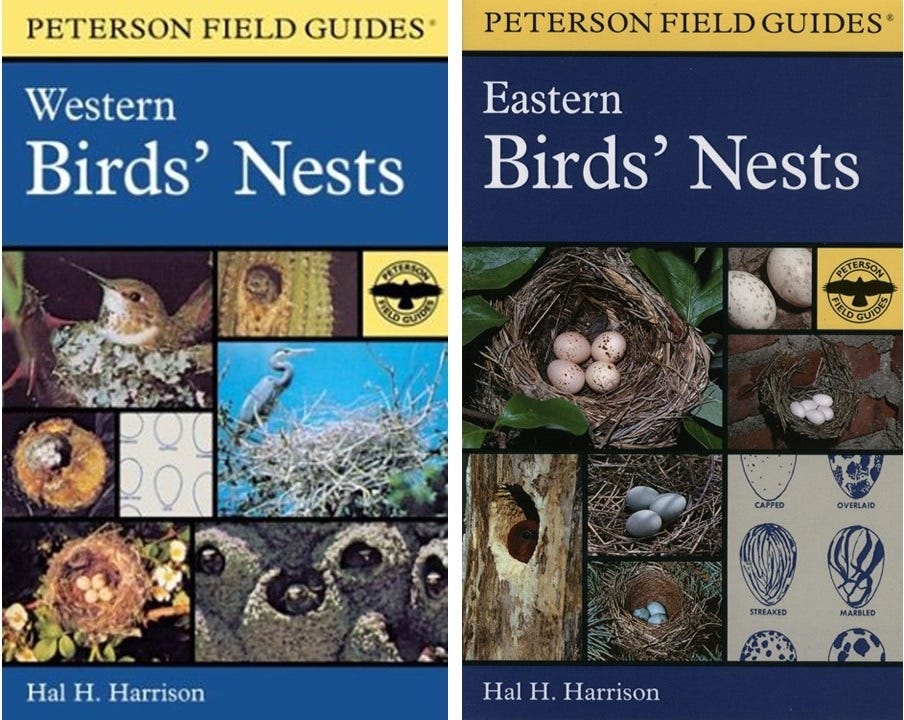

Identifying bird technology

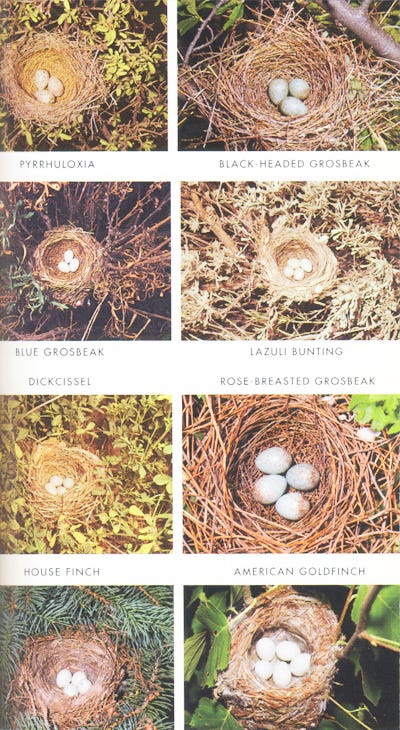

Western Birds’ Nests + Eastern Birds’ Nests

The baskets and fabrics made by birds are as admirable as their feathers. For years I’ve collected bird nests (a few in the image above) without knowing much about them. It took one obsessive Hal Harrison to find and photograph all of the nests and eggs of the birds in North America before I could begin to identify them.

Unfortunately, there is no real taxonomy for nest types, so identification is still a somewhat trial and error visual match. Environmental context — where a nest is found — is a bigger ID factor. But with some sleuthing in this book (two volumes, east and west) I’ve begun to identify species of nests. That has enlarged my appreciation of birds.

Oh, and these catalogs of many hundreds of nests also serves as splendid inspiration for human weavers. — KK

- The site at which the nest is located is often diagnostic. While some species will choose a variety of sites, many are highly specialized, and this is important in identification. Water Pipits nest on the ground in tundras; Chimney Swifts nest in chimneys, and White-throated Swifts nest in steep cliffs; all wood-peckers nest in tree cavities and so do Prothonotary Warblers; storm-petrels, kingfishers, and Bank Swallows nest in burrows; MacGillivray’s Warblers nest in low bushes while Olive, Hermit, and Townsend’s Warblers nest high in conifers; orioles build beautiful hanging baskets but Poor-wills build no nest at all.

- The nest itself is described in detail. Material used will vary with availability. For some species this has been noted, but readers should bear in mind that Spanish Moss would be no more available to a bird in Montana than spruce needles would be to a bird in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. The basic structure of the next of most species is so uniformly true to type that even though the materials used may vary, the format generally does not. An American Robin’s nest in Washington or Oregon with mosses built into it still looks very much like a Robin’s nest in Arkansas with mud and grasses predominating.