Land Use

Tools for Possibilities: issue no. 72

Once a week we’ll send out a page from Cool Tools: A Catalog of Possibilities. The tools might be outdated or obsolete, and the links to them may or may not work. We present these vintage recommendations as is because the possibilities they inspire are new. Sign up here to get Tools for Possibilities a week early in your inbox.

Pond-making how-to

Ponds can be used for swimming, wildlife magnets, irrigation, iceskating, fire protection, water gardening, landscaping, and fishing. You can build your own pond in your backyard, farm, or wherever.

Tim Matson is the established guru of building ponds with an earth-seal, rather than with a plastic or concrete lining. For 30 years he’s been creating, advising, and collecting knowledge about pond-making. His classic Earth Ponds (2nd ed.) is the basic how-to, and comes with a DVD. It supplies the needed lessons in siting a pond, building it, maintaining it, enjoying it, and also restoring old ponds. This is not your average how-to; it’s beautifully written and a joy to read. If you find the basics to your liking and need more, Matson has an updated Sourcebook with plenty of resources, and an illustrated encyclopedia of pond variations and building techniques. Finally, Matson has a helpful website with more videos and sources. — KK

- The sand drop is another well-esteemed pond keeper’s trick that takes advantage of the ice deck. It’s an upkeep technique well suited to older ponds in need of restoration, particularly where aquatic vegetation or mud get unruly. To set up a sand drop, the pond keeper spreads a two-to-four inch layer of sand–not salted road sand–over the ice. In spring when the ice thaws, poof! The sand falls in a uniform layer over the basin floor. Sand works like an inorganic mulch, shading out weeds and, like the finings in a beer crock, holding down sediment. In muddy ponds, it’s a good carpet material for the basin floor. One of my neighbors was able to use a sand drop to eliminate the slimy bottom in her family’s pond, along with snakes and leeches. True, the sand drop does fill in the pond to a minute degree, but it’s not often done, and it sure beats herbicides.

- Trout have a reputation as fussy feeders, picky as spoiled Siamese cats; yet for three years I’ve watched my brook trout gain weight without an ounce of supplemental feed. I see them feast on the bottom as much as in the air: the water is as transparent as an aquarium. I recall my neighbor’s drawdown and follow-up trout stocking: clearly, the fish were pitching in to keep it clean. And I recalled an old Vermont tradition: to keep the farmhouse water clean, a trout was dropped in the well.

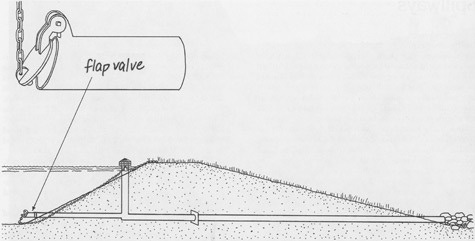

- Fixing low-tide ponds begins with a search for leakage. Ponds with piping often leak around the outside of the pipe or through seams, gaskets, and valves. In most cases, unless a fitting can be easily replaced, pipe repair involves digging up the line to repair joints or to implant anti-seep collars.

Scraping bottom in the pond basin Ray searches for flaws in the earth seal–clusters of pervious stone or gravel that would be the source of potential leaks. He carves out these patches and substitutes watertight soil. A good seal is the best defense against seepage. Pond makers who claim they can waterproof impossible sites with chemical additives and underwater dynamite blasts should run out of town. Like a potter’s bowl, the earth pond is molded with a blend of materials. In addition to drawing a sufficient supply of water, this site consists of good watertight soil: about 10 to 20 percent clay and an even mix of silt, sand, and gravel. Preliminary test holes in the pond basin are crucial in evaluating the worthiness of a site.

Sensible woodlot management

A woods can be managed to maximize recreation potential, or increase wildlife for hunting, or maximize timber. This guidebook assumes you’d like to optimize your woodlot’s timber potential in a sustainable fashion. Small-time woodlots with selective harvesting are a lot of work yielding little money, but with applied intelligence they can produce wonderfully rich and productive forests. This detailed manual will teach you intelligent woodlot management. What the author learned over 35 years is that you the forester should do as little as possible — just enough to encourage the woods to do as much as possible. — KK

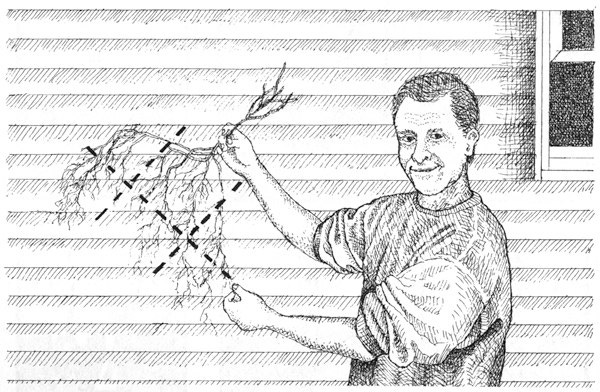

A typical oak seedling before trimming. Its roots are too long for spud planting.

- Some time ago, I surmised that I could establish an exciting mixed-species forest simply by planting as many seedlings of different varieties as I could fit in a given plot of land. As the stand matured, I could decide which trees to keep and which to cull, creating the mixture of trees I wanted. The stand would form an early canopy and the trees would side shade each other, meaning I’d never have to prune. Natural selection would favor the best trees to survive. They would become perfectly shaped veneer logs with little lateral branching. …By any reasonable standard of investment analysis, planting in this fashion is fiscal insanity. Yet this experimental plot promises to develop into a wonderful forest better than any other scheme I’ve witnessed for planting seedlings. It will require virtually no maintenance beyond thinning, which means it will flourish even if I do nothing.

- A site I had prepared for walnuts suddenly was inundated by giant ragweed, which grew to twelve feet in a couple of weeks, totally smothering all my seeded walnuts and oaks. Elsewhere I disced ash seeds between the rows of a walnut plantation. The ashes never appeared, but an influx of Queen Anne’s lace dominated the ground. Along a hedgerow of cedars I planted years ago, little cedars germinate in one particular spot and nowhere else. There must be something special about this spot (a “site-specific” condition, as ecologists and foresters say when they can’t explain such a peculiarity). Similarly, on property I own miles away from my main farm, I see new white spruces popping up next to their parents, while I seem to be incapable of making them germinate on my farm. The pH is not low enough at my farm, and conifers prefer acid soil.

- I have never seen or heard of a seedling that resulted in too many trees. Experts suggest that about fifteen thousand seedlings an acre is a good number, which means about three seedlings per square foot. I suggest that you plant whatever seeds you have.

- After having planted two fields next to a forest where squirrels stole every single nut in two successive years, I decided that I can live without walnut trees.

- You should also remember a suggestion I made earlier: Always cut the most inferior tree before cutting your best. You should upgrade your forest so as to maintain large, well-formed trees for future harvests. I urge you to be personally involved in deciding which trees are to be cut.

- Mark your harvest trees carefully. Most commonly trees to be harvested are marked with a paint gun by you or a forester. It is best to mark two spots on the tree: one at eye level to be seen by the logger and a second spot at the base to assure that only designated trees are harvested.

- An environmentally friendly method of getting logs to the logging roads is a system of winches and cables. Extracting logs by suspending them from cables does less damage to the forest than the use of heavy equipment. German foresters don’t allow skitters to move about in the woods, so all logs are dragged by cable to a logging road.

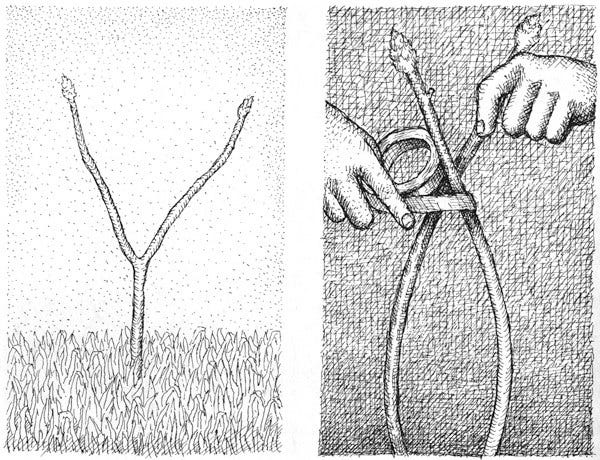

Taping a fork as shown will strengthen the branches. Later, you can remove one branch and the other will become the new leader.

02/5/24