Month: March 2020

03/2/20

03/2/20

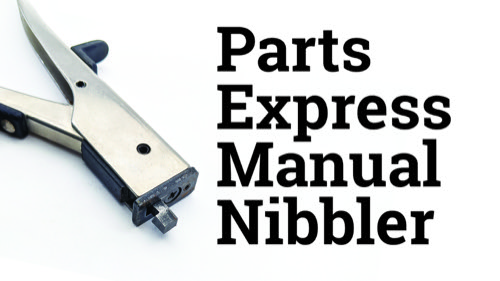

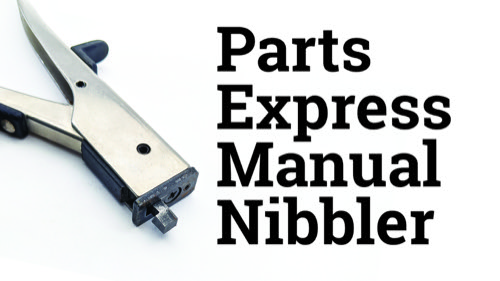

Nickel Plated Nibbling Tool

Make square holes for fuse holders, switches, indicator lamps, etc.

03/2/20

03/2/20

Make square holes for fuse holders, switches, indicator lamps, etc.

© 2022